2007, age twenty-nine:

I was standing by the open fourth-story window of my rented flat in Buenos Aires, as I’d been doing for hours on end in recent days and months, staring sullenly at the ocean of sidewalk below, a seeming resting place of final peace with just a slight shift in weight…

Buenos Aires sounds to most people like a romantic vacation destination, but to me, it was a place of retreat, a sign of my failure, a last step, at the end of the earth, on the way to the end of my line.

I had taken a wrong turn somewhere in life, and after a long, winding road, I’d finally hit a dead end, four stories up in an apartment overlooking the cracked sidewalks of the San Telmo neighborhood of one of the most storied cities in the world, and I was contemplating my final move.

I had suffered from recurring bouts of depression since high school. I won’t bore you with the details of my own teenage depression—in high school, there’s almost something wrong with you if you’re not depressed—except to note that it involved all the usual suspects: hundreds of pages of rants penned in various journals, unrequited lust elevated to the level of an existential condition, and of course, tortured anguish for a world so depraved and corrupt it could not recognize a truly special and unique literary talent walking among men, Michael Ellsberg, high school sophomore.

As college dragged on, however, and yet this same basic mentality remained, it all became less and less cute. A year out of college, I decided I needed help. I was living in New York, and one day at work, I picked up the Manhattan phone book, and searched under “psychotherapy.”

Thus began a fifteen-year journey through the entire gauntlet of Western medical approaches to mental health. This journey took me through psychotherapists, psychologists, psychopharmacologists, general practitioners, and psychiatrists, all with various diagnoses, suggestions, and prescriptions.

Early on in this process, I was diagnosed with depression, and prescribed Paxil, and later Prozac.

Certainly, the label of depression seemed reasonable, given that I often had difficulty even rousing myself out of bed to get to work. However, in the dialogues with various professionals leading to this diagnosis, neither the professionals nor I were paying attention to one detail about my life which—in hindsight—seems highly relevant:

On a modest salary as an assistant at a venture capital fund, I was—during my off hours—spending hundreds of dollars a week on sociology books at Barnes & Noble, conducting research for a book I wanted to write, a “grand unified theory of human society” that would put me on a level with Marx, Freud, Weber, and Durkheim.

(“I see… Hmmm… “ I can still hear various practitioners saying, in their practiced tones of non-judgment, scratching their chins while I explained my writing project in all earnestness. They then returned to their questioning about my depression symptoms)

Staying up until 3 or 4 AM the morning working on this “masterwork” did not help my relationship with corporate employment, and soon enough it became clear that my stable nine-to-five job and me were not really meant for each other.

At my wit’s end, I did what so many children blessed with compassionate, caring parents do in such situations. I moved back in with them, at age twenty-six.

My father needed help editing his next book. I’d edited his previous one (wordsmithing was about the only faculty I had any control over at that point), so the plan was to work for my father, while I picked up the pieces of my confused life.

I rented a room downstairs in my parents’ home—the same room in which I used to play Nintendo, trade baseball cards, and flip through shoplifted Playboys when I was thirteen. (I’d long since thrown out the Nintendo and the baseball cards.)

By age twenty-seven, I found myself routinely waking up at 2 PM on weekdays, in the room I grew up in, unable to rouse myself for my part-time job editing my father’s writing in his home office, in the room next door to my own.

I had virtually nothing to show for my half-decade out of college, save for a string of failed job attempts, romantic relationships that I’d mostly ruined myself, about fifteen hundred pages of rants in five volumes, and chronic under-earning that had landed me in tens of thousands of dollars in credit-card debt.

Something in my life had gone wrong—terribly wrong…

But what?

I rented a room downstairs in my parents’ home—the same room in which I used to play Nintendo, trade baseball cards, and flip through shoplifted Playboys when I was thirteen. (I’d long since thrown out the Nintendo and the baseball cards.)

One morning during this period, I simply could not get out of bed. After a twenty-minute struggle, I managed to break free of the chains of my bed, and walked up to the ground floor to cook some eggs for breakfast. When I got there, I could barely turn on the stove. I decided I needed to take the day off, and crawled back into bed.

I noticed, on my shelf, a book called Moodswing by Dr. Ronald Fieve. It had been sitting there for years, but I’d never read it. I started flipping through it as I sank back into bed.

Reading it, I learned of a manic-depressive condition called bipolar II. Unlike full-blown manic depression, also known as bipolar I, the highs in bipolar II are not manic but rather hypomanic. They feature extremely elevated mood, energy, and grandiosity, but they do not reach the state of psychosis (believing that you’re the second coming of Jesus, or that the toaster is sending you hidden messages, etc.), as in mania.

Nonetheless, Dr. Fieve wrote, the person with bipolar II can reach states of extreme excitement in which “judgment is lost.” Fieve described a type of “manic entrepreneur,” a patient who is “full of grandiose ideas and plans for business investments.” Most commonly, Fieve stated, the grandiose states of a bipolar II patient are “hypersexualized.”

This certainly seemed to describe me. Part of the reason I was unable to rouse myself from bed each morning during that period, was this:

I was staying up all night, often until 7 or 8 AM, working on my latest attempt to become a literary superstar. In that period, I wrote a wildly sexual, experimental, caffeine-pot-and-wine-charged attempt at autobiographically based comedic nonfiction, almost wholly devoid of any structure, weaving in manic political rants and fragments from my senior honors thesis in international relations at Brown. (The thesis was called “Black Masks, White Guilt: Cultural Appropriation, Multicultural Consumerism and the Search for a Meaningful First World Existence.”) My literary idols were Henry Miller, Hunter S. Thompson, and Michel Houellebecq. I was certain my name would be joining theirs at the table of “bad boys” in literature.

Here is one of the twenty-two rejection letters sent to my agent at the time. This dismissal was from a legendary literary editor who had discovered David Foster Wallace, in its entirety:

“I’m going to pass on this project. Mr. Ellsberg’s writing is not strong enough to overcome the simple fact that he is not a very likable person. Sorry, but there it is.”

Touché.

“I’m going to pass on this project. Mr. Ellsberg’s writing is not strong enough to overcome the simple fact that he is not a very likable person. Sorry, but there it is.”

Reading the description of bipolar II in Dr. Fieve’s book, a bolt of recognition hit me. I began ruminating over my past through this lens, trying to determine if the bipolar II description might apply to me. All of a sudden, I saw a whole pattern of grandiose, hypersexualized manic entrepreneurial projects.

A year out of college, I was working for my uncle at his venture capital firm in Manhattan. In an opportune moment of nepotism—did you know that “nepotism” stems from nepote, the Italian word for “nephew”?1—he set me up running a small venture capital fund of my own. I would manage a small amount of his own capital, investing it for him as I saw fit, so I could “learn the ropes of the industry,” he said. He would set up a limited liability company for this purpose, of which I would be CEO.

I decided to focus my company on environmental technology, because it was a hot and promising field, I wanted to improve the environment, and I wanted to show the ladies my sensitive side. I begged the administrative assistants at the firm to print up business cards that read “Michael Ellsberg, Founder & CEO, Green Planet Venture Capital, LLC”

Now I was ready to join the big boys, with women swooning and fawning over me, as befits a proper CEO. I ceremoniously changed my various profiles on different Internet dating sites—Match, JDate.com, Nerve, VeggieDate—from “analyst at a venture capital firm” to “CEO of a small venture capital firm focusing on environmental technology.”

I passed out my business card as if each one were a fraction of a date that were somehow all going to add up to a whole one. I gave them to waitresses and bartenders with my home number scrawled on the back. I gave them to department store saleswomen, administrative assistants, women I met at bars and clubs. Then I sat back, waiting for the flood of calls from the ladies who were hot and bothered for their CEO studmuffin. And. . . nothing.

Hypersexualized manic entrepreneurial venture? Check. Then there was BrainsBeautyWisdom .com. I’d registered that domain name, and put up a website. The idea was to build an Internet dating site devoted to older woman/younger man romantic relationships, of which I’d had several. (This was in 2003, before the phenomenon had tipped in the media.) I contacted several Internet-dating software designers for quotes. On the site, I constructed a page listing all of the books on that topic, and another page linked to various articles on the topic. Before I had any members or profiles on the site, I pitched More, a magazine for women forty and older, for a feature on the site.

When that idea fizzled, I briefly got energized by the idea of opening a dance studio in East Williamsburg. I’d moved out of my Village apartment after my uncle decided to let me go. (I didn’t blame him: Green Planet Venture Capital was nose-diving), and I was out looking to rent a loft in the up-and-coming formerly-industrial neighborhood of East Williamsburg. I found a ground-floor loft I liked. The real estate agent, a guy about my age, told me that the unit could be used for commercial purposes, and that many of the people in the building ran music studios, pottery studios, and other creative endeavors out of their lofts.

“Are there attractive women in the building?” I asked.

“Oh yeah, tons of them,” he said. “And in the neighborhood in general. All the artist girls are moving here.”

A light bulb went on: I’ll open a dance studio! Images of me teaching salsa dance to female artists in the neighborhood popped into my mind. (I had been an amateur salsa dancer and teacher for years.) I wrote a check for the first month’s rent right there, and signed the lease a few days later.

I began planning my business: I would call it “Mobo Dance & Yoga,” because the unit was near the Bogart exit off the Morgan L stop. I would teach a salsa class daily, and would rent out the unit for other dance and yoga classes: the women would flood into my place during the day!

I sank several grand from my savings into this scheme before I realized how absurd it was: I’d never operated a small business before, and I hadn’t even researched the market. It turned out, there was no market. While there were plenty of attractive bohemian women in the neighborhood, apparently they weren’t taking dance or yoga classes then, because a community art space a few blocks away—a business competitor I hadn’t even considered before impulsively signing the lease—had trouble getting three or four people to show up to their one yoga class and one dance class per week.

(This was way before the time when it would have occurred to me that my seductive intention behind this studio was super creepy. I’m very glad it didn’t come to fruition.)

Then there was Wing-Babes .com. I’d come up with the idea for a business in which men could pay $50 an hour for women to help them pick up other women in bars. I had even put up a website and even interviewed prospective Wing-Babes. Then my mother pointed out to me that any relationship that one of my male clients started with a woman he met in a bar this way would be based on a lie, as he’d have to lie about how he knew the “Wing-Babe” who had helped him meet his love interest that night. I saw her point, and I shut the business down.2

My mind seemed to dish up these hypersexualized manic projects, just as Dr. Fieve’s book described, with alarming frequency. I decided to see a psychiatrist who specialized in mood swings.

When I met with the psychiatrist, I told him that I had read a book about bipolar II, that this seemed to fit me, and that I’d like his opinion.

“One must be aware of what I call the ‘medical student phenomenon,’” he said right away. “Beginning medical students start reading the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual [the standard handbook of psychiatric illnesses.] They see the list of symptoms for each disorder, and they start thinking, ‘Does that apply to me?’ ‘Oooh, I’m sure I have that one. And that one too!”

I described my history: One grandiose plan or project after another. My multiply rejected book manuscript. Green Planet Venture Capital. BrainsBeautyWisdom .com. Mobo Dance & Yoga. Wing-Babes .com

After hearing me describe all this for half an hour, the psychiatrist peered at me, and said, “I have little doubt that what you are describing is bipolar II. Your self-diagnosis appears to have been correct.”

He told me that bipolar is often misdiagnosed as depression, because patients only go in to see the shrink during the depressed periods of the cycle, which are miserable. They never go to the shrink during the hypomanic phases (which I can confirm, are Grrrreat! Wow, the productivity!)

What’s more, he told me that these misdiagnoses are dangerous, as SSRI medications such as Paxil and Prozac can actually spark manic or hypomanic episodes in bipolar patients. So, the medicine I’d been prescribed earlier could very well have been making my situation much worse.

In later Internet research, I found several articles suggesting that—for unknown reasons—bipolar II is one of the most lethal of mental conditions, possibly more lethal than major unipolar depression and even bipolar I, with a suicide rate estimated up to 20%. (For example, one psychiatry journal article states: “bipolar II depression. . . carries the highest suicide risk among all subtypes of major mood disorders.”)

The psychiatrist recommended the standard medication for bipolar, lithium. I decided to try it. Within a few days, the most heinous, pea-sized green zits began appearing on my forehead. I had never seen anything like this before, so I typed in “acne” and “lithium” into Google. A quick search confirmed that this is a common side-effect of lithium. I promptly quit the drug; I felt I would have rather jumped off the Golden Gate than walk around with my face looking like a pea farm.

The psychiatrist switched me to lamotrigine, an epilepsy drug that also seems to work as a mood stabilizer for bipolar patients. Within a week, fists full of hair were turning up in my hands after shampooing in the shower. Back to Google: “lamotrigine and hair loss.” Turns out, it’s a rare-but-not-unknown side-effect. The idea of taking something that would have such an extreme and disturbing side-effect on my body was out of the question for me. I decided these drugs were not for me.3 I chose to hold off on the medication for the time being, and find a psychotherapist to help me with what was clearly an afflicted soul.

***

“Tell me about your parents,” Shoshanna, my new therapist, asked. It was 2005, and I was now twenty-eight.

“I don’t really feel like talking about my parents. They have nothing to do with this.”

“Your parents have nothing to do with your current issues? Don’t you think that’s a little extreme? We spend our most formative years with our parents…”

“They were good parents.”

“But that’s not the issue. I’m not suggesting they were bad parents. They could be good parents and still foster certain—”

“Oh, they probably have lots to do with it, for all I know. But I really don’t feel like paying to talk about them.4 I mean, they gave me the greatest unconditional love I’ll probably ever know—so we’ll come up with some story about now I’m on quest for that same unconditional love from women, and not finding it. But what if my parents had been cold and distant, and I came in here with the same issues? Then we’d come up with some story about how I’m seeking out the unconditional love I never got. It’s all just stories we tell ourselves, don’t you think? Just So Stories.”

Shoshanna frowned. Then shook her head slightly, letting out a small chuckle. “OK, well, we’ll just bookmark your parents for another time. Does anything else from your childhood seem obviously relevant to what you’re in here to talk with me about?”

“Oh, where do we do we begin?”

Shaggy Dog

Like many people, I harbored a deep sense of my unattractiveness to the opposite sex. I was un-athletic as a kid, and had zero interest in sports. This distanced me from my male peer group, and made me a lone wolf—a death sentence for attention from elementary school girls, who swooned for the most athletic boys with the most social standing among the other boys.

Picked on at school; picked last for sports teams. I was not academic enough to be a “nerd,” and not even cool enough to be a “geek.” I was just a dork. The nickname the other kids called me was “shaggy dog,” a reference to my unkempt big curly hair and my unstylish dress. I found solace in all sorts of strange, unsexy hobbies—practicing yo-yo tricks, juggling tricks, magic tricks—as if I had just thrown in the towel on being anything other than dorky. At a summer camp talent show, I juggled puffy shower sponges over the Doors’ “People Are Strange.”

A defining moment in my romantic development came when I fell into my first big crush, that same season at camp, for Marsha. At the Saturday night dance, I worked up my courage to walk up to her and tap her shoulder from behind. She turned around, and there, facing me in all her brightness, was my dream girl, whose attention I had for all of the next three seconds.

I crouched in and put my mouth near her ear so she could hear me over the blasting music, and asked: “Um, will you go with me?”, using then-prevalent fifth-grade lingo for something akin to “going steady.” The minor smile she had afforded me a moment earlier drained instantly from her face, leaving blankness, and even—I could sniff—a hint of horror.

“Um, I’ll think about it,” she said, in a flat tone. Then she promptly turned away from me and began dancing with herself again. Even at that virgin stage of my social savvy, I could tell, that was an obvious, “No.” I ran back to my bunk and started sobbing.

My friend Alex ran after me. “What’s wrong?’ he asked.

I told him about Marsha. “I’m never going to find my dream girl!” I sniffed through my tears.

“Don’t worry,” Alex said, in a remarkably mature tone for a fifth grader. “She’s out there, looking for you. You’re going to find her one day. Don’t give up. And when you do find her, you’ll forget about Marsha altogether; she won’t even cross your mind.”5

At camp, there was a reputed hut, called “The Hut,” in the hills above camp, where the popular kids reportedly snuck out at night and made out. I was never invited to The Hut, and I didn’t know where it was—though half an hour of hiking one day via the directions one Hut-goer divulged to me in confidence revealed to me that this Shangri-la did in fact exist: a triangular tarp with a few dirty camp mattresses under it. I sat on the mattresses, in daylight, imagining myself there at night, making out with Marsha. (If you wrap your arms around yourself, clasp your sides, and wiggle while air-kissing, you can create a reasonable solo approximation of what it feels like to make out.)

Seventh grade took a turn for the worse. I went from a relatively idyllic elementary school, to an academically- and socially-high-strung college-preparatory middle school in Oakland with the WASPiest name you could imagine, “Head-Royce.” At Head-Royce, I’m pretty sure you could have handed out an alphabetical list of our class, and asked all the students to rank the list from most popular to least—and all of our lists would have been close to the same. The pecking order was that well established—everyone knew their place—and I was in the dregs. A classic wallflower, at the school dances, I longed to be in the middle of the gym, slow dancing to “Nothing Compares to You” by Sinead O’Connor and “Vision of Love,” by Mariah Carey, like the popular kids.

For the start of eighth grade, I transferred out of the socially-stuffy atmosphere at Head-Royce, which I hated, to my local public school, Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School in Berkeley.

And then something bizarre and glorious happened.

Balthazar for a Month

I don’t know how this miracle happened, but somehow, a bunch of the girls at King Middle School projected “hot new guy” onto me when I got there. I say “projected” because I feel quite certain it was not anything I did myself to gain this status. My best interpretation is that all the romantic musical chairs had already been played out long before in this class (who had been together since elementary school) and that the girls were desperate for fresh meat.

And I was that fresh meat.

For a month.

One day, a girl I’d made friends with during the first few weeks of school, Annalisa, came up to me with a piece of binder paper, with hearts scribbled on it. She handed it to me. It had eight names of girls from our grade.

“What’s this?” I asked.

“These are all the girls in our class who like you.” Looking at that list was absolutely the greatest moment I had ever experienced in my thirteen years on the planet so far. Any one of those girls would have made a great girlfriend—that is, my first girlfriend. Annalisa was on the list—I had no idea she felt that way about me. And Vanessa.

Vanessa was a Queen Bee at the school—she was gorgeous, and a high-status ringleader. And taller than me. I don’t think I’d even spoken to her—just observed her holding court—and there was zero chance I would have ever thought I was in the running to date her.

And here I was, looking at a sheet of paper saying she—and seven other girls in the school—liked me.

“Which one do you want to go with?” Annalisa asked me.

I cannot exaggerate the effect this one sentence had on me. I had never “gone with” a girl before. I’d never even been on a date before. And here I was, being asked to choose a girlfriend from a list of eight attractive girls—a list including one of the most high-status girls in the school. WTF was happening?

Then I made one of the decisions I most regret in my life. I should have picked Annalisa. We were already friends, I really liked her, we had a fun vibe together, she was cute, and I’m sure I could have had a wonderful relationship with her.

But the egoic part of me… the part of me that was blown away that I could have a girlfriend as high-status as Vanessa, meaning that I was high-status too… that part of me said:

“I think I’m going to go with Vanessa.”

I’d never been in a situation before in which a girl I was friends with was asking me to pick between her and seven other girls for romance, from a list she’d handed me. I’m sure I could have handled it more gracefully. But ultimately, she asked me to pick, and I did.

“OK, I’ll tell her,” Annalisa said. She looked sad, but not crestfallen. I think she kind of knew that I was going to pick Vanessa. It was… after all… Vanessa.

The match was brokered by Annalisa on a Friday, and Vanessa and I arranged to go on a movie date the next day. We went to see Young Guns II. The movie choice was not random. Along with blue-chip nineties heartthrobs Emilio Estevez, Christian Slater, Kiefer Sutherland, and Lou Diamond Phillips, it starred an up-and-coming heartthrob named Balthazar Getty.

Balthazar (left) was just fifteen when Young Guns II came out in August 1990. He was devastatingly good-looking—a brooding bad boy crossed with pretty boy look—and had just become the “it boy” among teenage girls based on his starring role in Lord of the Flies earlier that year. He was on the cover of all the teeny-bopper magazines, and on posters on Annalisa’s wall.

And it turned out that—in a circuitous way—Balthazar had played role in my being handed the List.

The summer before, my father had taken me to LA, and on that trip, we stayed with his friend, the sixties radical activist Gisela Getty, for a weekend. I was thirteen, and her son Balthazar was fifteen, and had just become a movie star. Balthazar and his girlfriend, who was a model (she must have been older than him, as she could drive), offered to take me out for the night. For one glorious night, I went from being a dorky kid playing Super Mario Brothers and Duck Hunt on my Nintendo, organizing my baseball card collection, and whacking off to Playboy in my bedroom in Berkeley, to prancing around LA with a movie star, in a convertible driven by his older model girlfriend.

While thrilling—and Balthazar and his girlfriend couldn’t have been nicer—that weekend highlighted for me the unbridgeable romantic gulf between myself and a guy only two years older than me, who was vastly better looking, and famous. Yes, it was envy, but that word doesn’t do it justice: it was as if I was visiting an advanced alien in a romantically-faraway galaxy for a night. Does one envy aliens? Even more than envy, it was awe.

Early in the school year, before The List, Annalisa found out that my family knew Balthazar Getty’s family. She went apeshit. Before long, all kinds of girls in the school were walking up to me: “Oh my God, you know Balthazar Getty?! What’s he like?! Does he have a girlfriend?! Who is she?! Is he really that hot in person?!”

Of course, I liked the attention I was getting from girls—completely foreign to me—but it was also noticeable that I was getting this attention simply because of my minor acquaintanceship with another boy they were obsessed with.

At any rate, none of this mattered the Saturday night of my date with Vanessa. It was a night of many firsts. It was my first date ever. And I was on a date with one of the most popular girls in the entire class! It was my first time holding a girl’s hand. My first time putting my arm around a girl. I didn’t even have to get my “nerve” up to do it, as she was, well, sort of, my girlfriend. We hadn’t really “dated.” I had just… selected her. Ol’ Shaggy Dog went from never having had a girlfriend to simply selecting my girlfriend from a list. Taking her out had been as easy as… well… ordering take-out.

After the movie, we took the #7 bus up to her home in north Berkeley near mine. Her parents were away for the weekend. We sat on her parents’ bed, which had the biggest TV in the house in front of it. We watched it for a minute. Then we started making out. My first kiss. And it was much more than a little smooch. It was a full-on bed make-out. I was on top of the world. Balthazar wasn’t the star that night. I was the star of my own show!

That Monday, Vanessa and I sat together in the yard for lunch. Plenty of people were looking at us, making little comments. I had no idea what to say to her. What do you say to one of the most popular girls at school when you’re having lunch with her on Monday and she’s been your girlfriend since Friday, without any dating having led up to the relationship, and you’ve never had a girlfriend before, and people are watching you? I put my arm around her, but I felt her stiffen up, so I took it away.

The next day, I went to meet her for lunch, and she informed me that she didn’t want to go together anymore. She wasn’t mean about it—she just said it matter-of-factly, as if she was telling me the weather had changed. She didn’t give me a reason, and I didn’t ask. I knew what the reason was. I was a fucking dork, and that didn’t change over one weekend. As soon as she saw how awkward I was with her at lunch—without the distraction of seeing the movie with Balthazar in it or the make-out afterward—she saw that I was not in her league. It made perfect social sense; I didn’t question it. I was simply not Vanessa material.

And… as went Vanessa, so went the rest of girls at King Middle School. As soon as she rejected me, I became a persona non grata on campus. I had gone from social obscurity at the start of the semester, to the most desired guy of the moment among the girls in the class, to the short-lived boyfriend of one of the most popular girls, to a social reject, all in the space of about a month. Romantic whiplash.

Even at that age, I wasn’t naïve enough to think that Annalisa would still take me as her boyfriend if I came back to her after Vanessa dumped me. So I didn’t ask. But I was disappointed to find out that either my choice of Vanessa and/or my being dumped by Vanessa meant Annalisa no longer wanted to be friends with me at all. She ignored me the rest of the year, as did all the other girls in the class.

I spent the rest of that school year wondering what would have happened had I chosen Annalisa instead of Vanessa. I probably would have had a girlfriend that whole year—a real relationship with a nice, kind, sweet, friendly, cute girlfriend. Instead, I allowed myself to get seduced by the promise of status and social power.

It wouldn’t be the last time.

Rock Star Envy

I explained to Shoshanna—as she listened, perhaps exasperated by this litany of my woes of envy—that while I was in college, a young A-list rock star bought the house behind my parents’ house in Berkeley.

He was the lead guitarist for a band whose first album had gone multi-platinum a few years earlier. I didn’t find out the way you might expect to find out that a rock star had moved in behind you—groupies, paparazzi, all-night parties. Rather, my friend Arnold told me. Arnold’s older brother had gone to high school with the Rock Star, and was still friends with him.

Five years before, I heard through Arnold, the Rock Star had been serving frozen yogurt part-time in Berkeley, playing in a rock band on the side. Then his band got discovered and signed by a major label. Their album went multi-platinum, their single flew to the top of the charts, they started touring all over the world, and the Rock Star bought his first home, behind my parents’ home.

I only met the Rock Star once; he had been kind enough to invite me to a party of his. (Likely the only time I will have the experience of creeping through a hole in my backyard fence, where I used to shoot BB guns, to get to a megastar’s party.) Through Arnold, I heard details of the Rock Star’s new, super-charged sex life. He went around saying things to Arnold’s brother like, “Damn, I haven’t had sex in a week. Oh, except for those two blowjobs I got.” One time, the Rock Star was in a bar in Berkeley, and a woman walked right up to him and said, “I want to suck your cock.” Within a minute, he was in receiving a blowjob in a bathroom stall.

I reacted to these tales the way an agricultural laborer in the developing world who earns $500 a year might react if he heard that I and lots of people in the developed world are spending the value of his annual earnings in a month to sit on a couch and tell a stranger how miserable we are for fifty minutes a week. Anger, resentment, envy, wonder.

If, after telling this agricultural laborer about how some people in the developed world spend his $500 annual income, you handed him a stack of People magazines, he might start poring over them obsessively. He might immerse himself in a fantasy world, full of glamour, beauty, and excitement. Even if his station in life satisfied him—maybe his neighbors only made $400 a year, and he felt proud of his extra $100, part of which he used to send his kids to school and the rest of which he used to buy his wife nicer clothing—he wouldn’t feel satisfied for long after reading all those issues of People. (I read later that psychologists refer to this dynamic—in which people judge their level of material abundance in comparison to others—as “relative deprivation.”)

Every time I looked out of my window, onto the Rock Star’s home, I wondered about what lucky things were going on inside. Was he on his bed right now, with two gorgeous, naked women, making love to one of them on his back while the other sat on his face while the two women kissed? Was one of them bent over in front of him, with her head between the other’s legs?

This was the period I started writing Rock Star Envy—to deal with my emotions from contemplating the differential between the five-finger sex going on in my bedroom, and the five-groupie sex going on in his, separated only by my parents’ backyard.

***

One day in therapy, after I had been prattling on about whatever I imagined was going on in the bedroom across the backyard from mine, Shoshanna asked me, “How many women have you slept with, approximately?”

“Thirty-seven.”

“You keep a list?” she asked.

“Not quite. I keep a journal. I always write a journal entry about my first time sleeping with a new woman. In case I ever forget what it was like—I want to remember.”

“Well, if it means anything to you, as far as I can tell, that’s a lot more women than the average man has been with,” Shoshanna said.

“Whoop-de-fucking do!” I joked, twirling my finger.

“Isn’t your goal to be some kind of super-stud? It doesn’t matter to you that you’ve slept with far more women than probably most guys have?”

“The problem is,” I said, “there’s a power law curve. Even if I were sleeping with ten times the women that the average man does, it doesn’t matter—we’re all just peons on the long tail of the power law curve.”

“What are you talking about?” Shoshanna asked, eyebrows raised.

“Have you heard of a guy called Tucker Max?”

Shoshanna said no, but lightly rolled her eyes, as if to say, “Oh God, what is this going to be? Here we go again…”

Envious of an Asshole

In the mid-aughts, in one of the peak periods of the relentless manic-depression of my twenties, I turned my writing gaze inward to focus on my neurotic self-judgment as a beta-male and my envious obsession with the sexual access of successful, famous alpha males. I titled the mess of the manuscript I was working on—what else?—Rock Star Envy. (I described it as “Manic Nonfiction.”) I had a literary agent who was sending it out enthusiastically, but we were racking up rejection after rejection.6

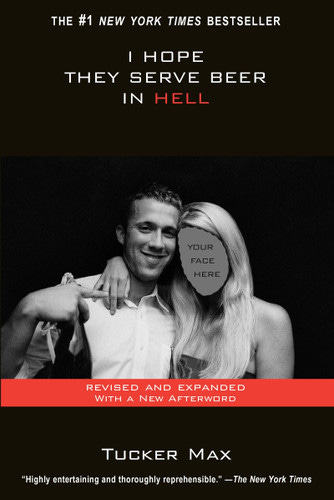

During this period, I came across a New York Times article about a nonfiction writer who was having far more success than I was—both in publishing, and in dating (or rather, in hooking up).

The author was Tucker Max, bad-boy partier who chronicled his drunken exploits on his blog, and who had published a book of his true-life adventures, I Hope They Serve Beer in Hell, which had become a bestseller. (The book’s cover featured Max with a beer in one hand and his other arm around a seemingly-attractive blonde, whose face was cut out with dotted lines. “Your Face Here” the cutout read. He refers the genre he pioneered as “dick lit.”) The introduction to his website read:

My name is Tucker Max, and I am an asshole. I get excessively drunk at inappropriate times, disregard social norms, indulge every whim, ignore the consequences of my actions, mock idiots and posers, sleep with more women than is safe or reasonable, and just generally act like a raging dickhead. But, I do contribute to humanity in one very important way. I share my adventures with the world.

The New York Times article, entitled, “Dude, Here’s My Book,” described the sexual opportunity that Max had created for himself through his combination of extreme macho arrogance, and his literary success and fame:

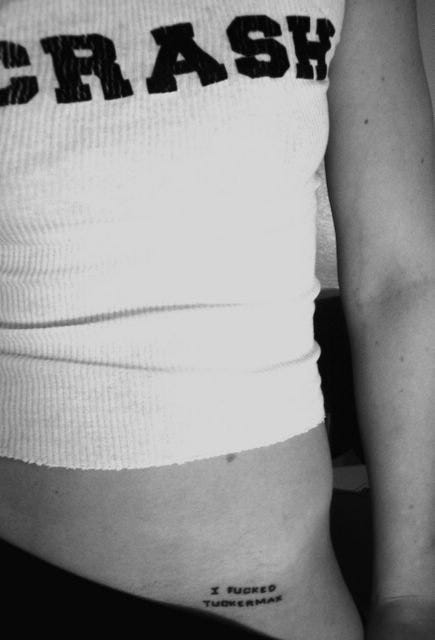

“I Hope They Serve Beer in Hell,” has sold over 30,000 copies since and has helped make Mr. Max a celebrity on college campuses. He said he gets as many as 400 e-mail messages a day, including an average of five offers of sex from women, which he accepts whenever practical. One of Mr. Max’s conquests got a tattoo on her groin boasting of their liaison in candid terms. True to form, Mr. Max wrote up the episode for his Web site as well.

On his site, he had a “Hook-Up Application Form” where women could “apply” to hook up with him when he was in their town touring for his book. I cannot overemphasize the negative psychological effect reading about his five offers of sex a day and his hook-up application form had on me. I felt like a worthless loser. I couldn’t get my book published, and here was this guy who not only had a published book, but who had so much sexual opportunity that he literally had to turn some women down who were filling out a form to apply to hook up with him.

And he was an asshole. (His subsequent book of more exploits and conquest, now supercharged with his literary fame and status, was entitled Assholes Finish First.) The pattern, as described in his stories, was that he would treat women like shit, calling them sluts and whores and making all kinds of extremely objectifying judgments about their looks, and the women would fling themselves at him on account of his brashness and dominance. (See one account from the perspective of one of these women: “I Slept With Tucker Max, the Internet’s Biggest Asshat.”)

One woman he treated like shit was so taken with her night with the tough guy, she got a tattoo—the one alluded to in the New York Times article—that said “I Fucked Tucker Max.” She was so proud of this erotic accomplishment she created an “I Fucked Tucker Max” blog site.7

I was, at least in theory, a “nice guy” and a “sensitive guy”—the guy who supposedly cares about women and is utterly flummoxed as to why women seem to prefer jerks who treat them like shit, while they put the supposedly nice, kind, caring (but meek) guys who believe they would treat women much better, in the dreaded “friend zone.”

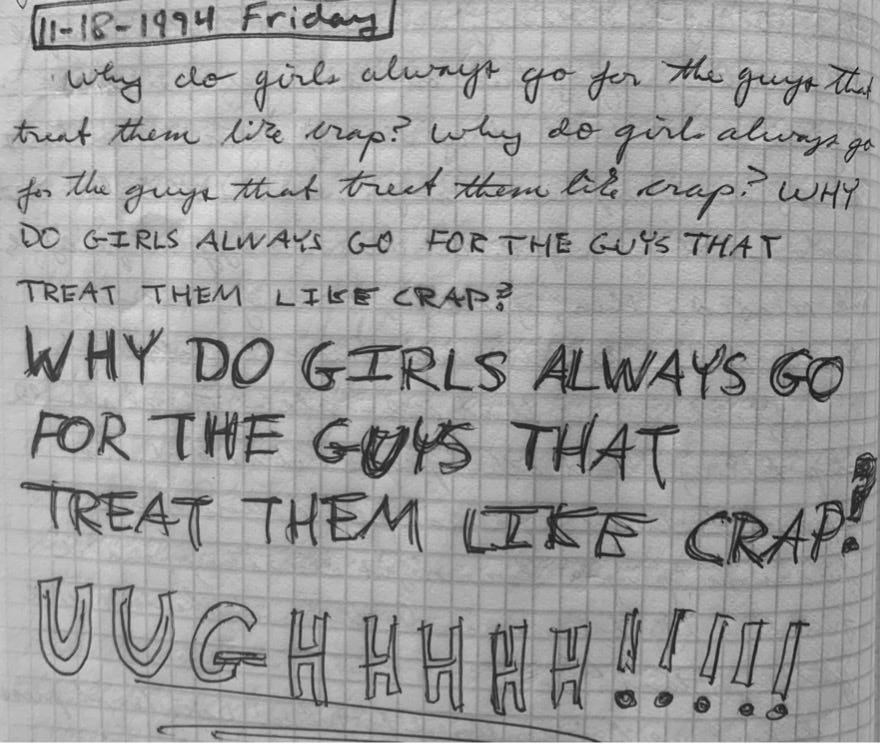

During my senior year in high school, my best friend Christina—a fellow hard-core vegan activist whom I had a massive secret crush on—went for a friend of mine at our school named Vincent. He was taller, way more athletic and better looking, and far more confident than me; I envied him wildly. He was a total ladies’ man, girls swooned around him, and he was making the rounds of the girls in our class, hooking up with them and then ditching them, leaving them heartbroken, and moving on to the next one.

When he got around to Christina, she went for him immediately, in contrast to her months of expressing no romantic interest in me, which I desperately wished she would do based on our endless vegan discussions. “I’m so confused,” I wrote in one of my journal entries, as I watched this play out between them:

I mean, I have every characteristic that I think would appeal to Christina—I’m vegan, spiritual, sincere, intellectual, and gentle. Why isn’t she crazy for me like I am for her? The only thing I don’t have is Vincent’s good looks or his confidence. Maybe that’s all she wants: good looks and confidence, not the same environmentalist values or drive to stop the torture of animals.

As I watched with envy the short-lived romance between Christina and Vincent play out (before he moved on to his next conquest, as I knew he would), I inked the following in my journal:

I was not then self-aware enough—either in high school or in my twenties when the whole Rock Star Envy and Tucker Max thing was playing out—to realize that usually the self-proclaimed “nice guys” and “sensitive guys,” including myself, objectified women just as much as the macho assholes. It’s not like we were going for women at our own attractiveness and status level—we wanted the hotties, and the high status that went along with them, as much as everyone else did.

The macho assholes like Max were just more open about their superficiality and objectification. In one way, the assholes were less bad: at least they were offering “truth in advertising” in terms of what they were after and what they were offering women, and the women who chose them knew exactly what they were getting. (Informed consent.) The “sensitive guys,” including myself, were usually engaged in some kind of unconscious “false advertising”: presenting as caring and kind, but secretly envious of the status and sexual conquests of the jerks.

The M.O. of the nice guy was the unconscious bait-and-switch. The exterior of “kind and caring” was the bait, and the interior of being an objectifying, entitled, whiny jerk was the unconscious switch. The latter would often rear its head if we nice guys were given even a wisp of opportunity to be romantically involved with the women we craved. It’s not that the nice guys were intentionally trying to be jerks—our conscious self-image was exactly the opposite. It’s that—unlike the asshole—the nice guy wasn’t aware of his demons within, and thus when those demons finally got unleashed from their years of repression, they came out hard, and caught by surprise the woman who was drawn to the “kind” exterior.8

“I guess that’s why I’m here, sitting on your couch.”

In response to Shoshanna’s question about what I meant by my “power law” comment, I replied:

“Tucker said he’s lost count of how many women he’s slept with. He said it’s likely over a thousand. [The Rock Star] is likely over a thousand too. I’m sure Bathazar has had hundreds of models. I’m at thirty-seven women.9 And it’s not as though there’s a straight line between guys at my level and the guys at the top. It’s the same ‘social proof’ I was trying to scheme via Wing-Babes, but these guys have it exponentially. At a certain point, these guys get so successful with women, that other women want to be with them just because other women want to be with them. I think Rene Girard called it mimetic desire—desire for someone aroused by the fact that other people desire the same person. The winner wins by exponentially more than the guys like me. It’s a winner-take-all game.”

“Why is this a competition for you?” Shoshanna asked.

“I mean, I could be some fucking loser, a nobody content to be forgotten when I die, as if I never existed.”

“What does how many women you sleep with have to do with that?”

“Because sleeping with lots of hot women is a sign that you’re a somebody. Hot women don’t sleep with losers. They don’t want to reproduce the genes of losers.”

“But you don’t even want kids!” Shoshanna exclaimed, in that exasperated tone that was often therapeutic for me to hear (how ridiculous I was being).10

“I meant that theoretically,” I said. “It’s the principle of it. There are winners in life, and there are losers. The way male winners are determined is by how beautiful the women they sleeps with are, and how many of them they sleep with.”

“Whatever you say about this ‘power law curve’ theory, thirty-seven women is a lot of women.11 You’re not some guy who can’t get a date. You’re just not. You may have been that guy in high school, but you’re not that guy anymore. Your self-image is stuck in the past. That’s not uncommon at all; in fact, it’s more common than not. But it’s steering you wrong now. You’re fighting yesterday’s battles, playing them out again and again—and not seeing how being stuck in the past is harming you now.”

“How is it harming me now?” I asked.

“You’ve described some of the women you’ve been with recently. They seem like perfectly nice women. If you weren’t compensating for your status issues from your teenage years, maybe you’d see the women who are right in front of you, and stick with one of them. Instead, you’re ditching them after each conquest—and that’s what they are, conquests—because you want more and more of them. You’re trying to prove to yourself that you’re not that ‘loser’ version of yourself you hated in middle school and high school.”

I took that in. She had a point. I couldn’t deny that.

“But,” Shoshanna continued, “in trying not to be that loser you thought you were as a teenager, you’ve swung the pendulum. You’re mimicking the exact behavior of the asshole guys you judge yet secretly envy. You’re practicing the same love-em-and-leave-em behavior you judge in these guys. Is that who you want to be?”

“It’s worse,” I said. “I’m mimicking them, taking on all their terrible traits, yet I’m not even having the success they are. They’re assholes and winners. I’m being an asshole, but I’m a loser.”

“Listen to yourself, Michael. Just listen to yourself,” Shoshanna said. “You need help man,” she said, shaking her head and chuckling under her breath.

“I guess that’s why I’m here, sitting on your couch.”

Replication Desperation

I should probably clarify something here, as it bears on why I was close to suicidal at times throughout my twenties. My comment to Shoshanna about how I would die an unknown loser, and that other guys would have their genes reproduced by lots of hot women sleeping with them, is strange on its surface, given that I was pretty sure I didn’t want to reproduce genetically—a strangeness which Shoshanna picked up on.

What gives?

My depression in my twenties—and later again in my thirties—was what I later found out is often referred to as an “existential depression“: in my darkest moods, I thought there was something wrong not just with my existence in particular, but with existence itself. While much of my depression during this time had to do with feelings of being a failure, a loser, and (relatively) unsuccessful with women compared to the rock stars, movies stars, and bad-boy alpha males I envied, there was a deeper cut: a sense of the utter futility of this entire charade called life.

It was a double-whammy: desperately feeling like I was losing a certain “game” of life, while at the same time realizing that even if I “won” this game it would be meaningless and pointless. And self-hatred for even wanting to win this pointless game—while at the same time still desperately wanting to win it.12

My sense of life as a series of competitions for replicational dominance, and my sense of the futility of life itself, filled as it was from top to bottom with such competitions, came from reading—cliché of cliches—The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins.

Contrary to the impression given by the (poorly chosen) title, the book does not argue that genes necessarily make humans selfish. Rather, Dawkins’s point is that genes themselves, as individual entities, are selfish, meaning they have one function, and one function only: to replicate themselves at all costs. Any gene that does not display this function gets out-replicated by those that do, and eventually disappears.13 Dawkins, like a good Darwinian, suggests that the universal principle of life—likely to hold anywhere life is found in the universe—is that “all life evolves by the differential survival of replicating entities.”

Yet, in the final chapter of the book (which famously introduced the concept of the “meme,”) Dawkins argues that genes are not the only replicating entities found within life in the universe. Rather, he argues, a second replicator can be found right here on Earth: a “unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation” rather than of genetic replication. Dawkins calls such units of imitative copying “memes,” based on the Greek root mimesis (which means “imitation, representation.”)

Dawkins writes:

Examples of memes are tunes, ideas, catch-phrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches. Just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool by leaping from body to body via sperms or eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain via a process which, in the broad sense, can be called imitation. If a scientist hears, or reads about, a good idea, he passes it on to his colleagues and students. He mentions it in his articles and his lectures. If the idea catches on, it can be said to propagate itself, spreading from brain to brain. As my colleague N. K. Humphrey neatly summed up an earlier draft of this chapter: ‘… memes should be regarded as living structures, not just metaphorically but technically. When you plant a fertile meme in my mind you literally parasitize my brain, turning it into a vehicle for the meme’s propagation in just the way that a virus may parasitize the genetic mechanism of a host cell. And this isn’t just a way of talking—the meme for, say, “belief in life after death” is actually realized physically, millions of times over, as a structure in the nervous systems of individual men the world over.’

There are many reasons one might find this worldview depressing. For me, the reason that hit hardest was the idea that life is, in essence, “replicating entities.” I thought “Replication is just so… meaningless. You have one thing, and now you have two of them. And now you have four, and eight, and sixteen. Where is the meaning of that? Replication itself is neither good nor bad, it just is. Its goodness or badness depends on what is being replicated—yet judgments of goodness or badness are themselves just memes vying for replication like any others. Just because something is being replicated a lot doesn’t mean it’s good, and plenty of things that are good don’t get replicated much. But if something good doesn’t get replicated, it dies out, and that can’t be good… And I want my idea memes to replicate, and I want the success that comes from that… even while I know it’s ultimately just a meaningless game for replication dominance… AAAAARGH!”

I thought of this mental state I would get into as “replication desperation.”

I was a man of many hungers—for sexual power, status, and fame, mostly—and yet Dawkins’s book got me to see that these hungers basically just served the whims of various replicators, whether genetic or memetic. I was, more or less, just the bitch of one replicator or another. And the people who were the servants of more successful replicators got more rewards in the form of fame and sexual status and money and power.

And I wanted those rewards—just because the replicators driving me knew that doing the power-hungry things to get the rewards would serve their replication. And that the rewards themselves would attract more rewards, because fame feeds on itself, sex feeds on fame, fame feeds on sex, sex feeds on power, power feeds on money, money feeds on sex, and sex feeds on money.

Feeding, feeding, feeding.

And yet still so hungry.

Sometimes I would get so disgusted with the constant feeding frenzy in my soul, I would feel this dramatic, sudden, involuntary unplugging from inside of me. These were the depressions—usually a few weeks or months at their worst. “What’s the point?” I would wonder.

“Why keep engaging with this charade? If I keep going, the best outcome is that my memetic ideas will replicate more, which might make me slightly more famous, which might get me more sexual access, which will make some part of my brain happy, the part that gets happy when I’m doing things highly associated with genetic replication—even though I don’t even want to genetically replicate. All of this is so fucking annoying, and endless. When will it end? Given the pointlessness and futility of the replication game, even for the winners, why not just opt-out early—the big ‘opt-out’—and save a whole lot of pointless struggling in the meantime?”

The one thing that kept me from offing myself when I was in these existentially depressed states was knowing how much grief this would cause my parents. They were good parents—they loved me unconditionally and supported me in all kinds of ways—and we were as close as parents and child could be.

The thought of sending them into deep grief for the rest of their lives—to have that be the last part of their life story after they had lived such long and rich lives—after all of the genuine love and care they showed me, made me cry. So I felt stuck. I didn’t want to cause these people I loved tremendous pain, but that meant I had to keep walking through all this inner pain.

After a few weeks of lying in bed or ambling around in roughly this mental state, some switch in my mind would flip, and all of a sudden… ladies and gentlemen… It’s Mania Time!!!

This switch would usually flip when I got some idea or concept or scheme that I thought would once and for all help me win the sex-money-fame status game. Maybe, in my depression, I had been reading vaguely Buddhist-inspired self-help literature encouraging me not to feed my “hungry ghost” within… to humble myself… to renounce my drive to achieve status, success, sex, fame, money, and power… to see these as addictions (addictions that were destroying the planet!)… to stop feeding the addictions. To sit on a pillow. Watch my breath. My boring breath—nothing exciting about it at all. Not nearly as exciting as hot babes! And I would resign myself to this boredom and humility—this nothingness, this death, from a memetic replication perspective—for a few weeks

Then, one day, while sitting on a pillow, trying to accept that I’m a nothing rather than fight it… I would have some “spiritual insight”… and I would be sure that I needed to share it with the world! This is going to help so many people! I could write a book about this, teach a course! I could create a method, trademark it! Women will love it!14

I began to understand why bipolar II was considered among the most lethal of mental conditions. Bipolar II is the mental illness of getting your hopes up dramatically and have them whisked away just as dramatically. Like Charlie Brown hoping that this time is finally going to be the time Lucy’s not going to whisk the football away from him at the last minute, and he’s finally going to get to kick it, and then… fuck… flat on his ass… fooled again. Bipolar II is the mental illness of repeatedly being a fool, and then getting depressed that you’re a fool… and then getting excited by some new foolish way to stop the foolishness. Eventually you get tired of the rollercoaster, and start thinking… what’s the point?

Bipolar in Buenos Aires

2007, age twenty-nine:

As is often the case with mental issues, they combine with poor work habits to lead to low earnings. By this point in my life, I had developed some other freelance editing gigs beyond working for my father. But still, my earnings this late in my twenties were laughably low, and were only livable because I was living in the room I’d grown up in. (Or rather, the room I’d failed to grow up in.)

I did have one thing going for me, though. As a freelance editor, my work could be done from my laptop, anywhere in the world there was an Internet connection. I had editing clients across the country, and even a few internationally, and none of them cared where the hell I was, as long as I did the work well and got it done on time.

A friend from college had moved down to Buenos Aires in 2003, and she had been telling me how livable it was there. This was 2006, five years after Argentina’s cataclysmic economic crash. I spoke fluent Spanish, from studying in elementary and middle school and a high-school year abroad in Spain, so language wouldn’t be a problem. For $15,000 a year, I learned from research on expat sites, I could live very well down there—my own one-bedroom in a nice neighborhood, meals out once or twice a day in nice restaurants, theater and entertainment, taxis, good wine, world-class steak—all in a modern, European city considered by many to be one of the most romantic in the world.

That was right around my annual budget. It was time to move back out of my folks’ place—before I turned thirty—and try my hand at supporting myself fully again. I told Shoshanna of my plans, and she was supportive; we would continue sessions over Skype.

So, with laptop and one suitcase in tow, in January of 2007, I was off to Argentina: an economic migrant taking the best option available among what seemed to me a limited palate of options.

***

Life was good for a while in Buenos Aires. As promised on the expat sites, I was able to find a clean one-bedroom apartment, fully-furnished, with high-speed Internet connection, for $550 a month.

I spent my days working on freelance projects for US clients via my laptop in one of the many trendy local Wi-Fi cafes in San Telmo, sipping on rich $1 cups of café con leche. A $5 bottle of world-class malbec split with a tourist woman checking her email in the cafe—then perhaps a cone of Argentina’s world-famous gelato with my newfound tourist friend after dinner.

Yes, life was very good.

Until it wasn’t.

My mood swings started getting worse and worse. Dark clouds pressing me down into bed, making it almost impossible to rise up to start the day—punctuated by manic bursts of all-night re-writing of Rock Star Envy (after it had already been rejected 22 times years earlier), in which I became convinced I was the next Henry Miller or David Sedaris. Difficulty rousing the energy or motivation to earn enough to support myself even there. Frequent bouts of hours staring out my fourth-story window at the ocean of the sidewalk below, a place of final peace. The only thing that ever kept me from shifting my weight just a little and ending it all was thinking of the call my parents would get, informing them that their son’s brains were splattered on a sidewalk in Argentina and asking where they should send the corpse. That would be just too much. That would be cruel.

So I would step back from the window when the pain of that thought hit me. . . .

Footnotes:

From Etymonline: “Originally, practice of granting privileges to a pope’s ‘nephew’ which was a euphemism for his natural son.”

Unfortunately for the world, some guy copied my business idea and my site, almost word for word, and ran with it. He had huge success with it in the media, getting featured in the New York Times, the New York Post, the Montel Williams Show, and Good Morning America. This guy’s business even formed the basis for a TV show called Love, Inc., on UPN. Even though I knew—thanks to my mother pointing it out—that it was a shitty concept that never should have seen the light of day, I still felt tremendous envy that this guy got so much fame and attention for my shitty idea; I had one of my most serious mental breakdowns of this period over this internal conflict between my ethics and my envy.

I am not recommending for or against this decision for anyone else—these drugs help many people, and without side-effects. This was simply the decision I came to for myself. However, one important point: I was under medical supervision when I made this decision. I definitely do NOT recommend stopping a medication without talking to a doctor first; if you are currently on medication, doing so could be extremely dangerous, and potentially life-threatening.

A more accurate statement would have been, “I don’t feel like having my parents pay for me to talk about them.”

His words were prophetic. Except, that is, the forgetting part, as Marsha’s rejection was the subject of hundreds of dollars’ worth of pathetic therapy sessions. And now finds itself memorialized in a book.

Looking back, I’m extremely thankful it never got published, as it was a fucking mess. I was young and immature, both as a writer and as a person.

Around five years later, in 2011, I met Tucker Max at a publishing conference. We struck up a conversation, and he mentioned that he was in psychoanalysis four days a week to deal with his trouble forming and keeping intimate bonds with women, and concurrently he was giving up his hard-partying ways (as well as his signature writing about his partying and womanizing). Instead, he looking to settle down, get married, and have kids. He had not disclosed any of this publicly, and I thought it was all fascinating. I asked if I could interview him on all this, and he agreed. The result is this interview on Forbes: “Tucker Max Gives Up the Game: What Happens When a Bestselling Player Stops Playing?”

At the end of our interview, after he shared with me vulnerably for the whole day, I shared with him a bit about my own journey of envying his alpha-male success with countless women, and how I eventually let go and came to terms with that, found an amazing woman (Jena), and married her. I mentioned that I still had a tinge of that former envy, that I was having trouble getting rid of.

He gave me the following advice (quoted in the interview):

What your unconscious is doing [when you seek validation from womanizing] is expressing that childhood trauma through achieving some ‘win’—‘Oh, if I’m attractive in this bar to this woman I don’t even know or care about, then it makes up for being a picked on as a kid.’

Well, it doesn’t, dude. I’ve sold millions of books! I’ve had sex with hundreds, maybe thousands of women. And I still had to go to analysis! I started analysis after all that dude! That shit didn’t fill the hole man. None of it did. I thought it did for a while, and it didn’t. Because the hole was created by a different sort of pain, I thought this other stuff would make up for it. But that’s not how it works. It’s not like a scale that balances out—some bad stuff from the past gets balanced out by some good, different stuff now.

No, that’s not how it works. Either you address those issues and you change those patterns, or you don’t. And nothing you dump on top, no amount of attraction from any woman in any bar is ever going to change how you unconsciously feel about things that happened to you when you were a kid on a playground.

You have to deal with those feelings directly. You can’t deal with them in a bar. I wish you could man! Because, if it was possible to cure your problems with pussy and drinking and book sales, I would have done it! I would have fuckin’ done it, dude! I wish, man! I wish! But I couldn’t. And neither can you.

In later years, a whole feminist analysis of the problems with the “nice guy“ and the “friend zone” concept developed online. See, for example, the “Nice guy syndrome“ entry at the Geek Feminism Wiki.

See the objectification by the self-proclaimed “nice guys” or “sensitive guys” who complain about getting “friend-zoned”? It pervades the entire consciousness of the “nice guy,” yet he is oblivious to it.

I’ve tended to choose therapists who are willing to talk and emote frankly to me. I invite them to share their honest perspective on what I’m saying, with no beating around the bush. I find this more therapeutically productive—and more fun—than the therapist taking a purely neutral stance.

How did I meet all these women, given my persistent self-image as a “loser”? Two ways, one wonderful, and one horrible. First, I devoted myself to salsa dance. This is a fantastic, totally above-board way to meet women (as is any form of social dance), one that I would recommend to any guy looking to improve his confidence and dating opportunities with women.

Second, I dove into pickup artistry (PUA) in 2000, when I was twenty-three, and stuck with it throughout my twenties. I now see PUA as toxic and vile, rife with sexism, manipulation, mind-games, and an extremely objectifying, using/taking attitude towards women. I now actively advise men against going anywhere near it. I deeply regret my involvement with PUA; if I had it to do over again, I never would have touched it.

At the time, I came across a passage in a “fictional memoir” called A Fan’s Notes, by Frederick Exley, that captured some of this damned-if-you-do-damned-if-you-don’t inner conflict I was feeling. The anti-hero Frederick is a self-identified depressive loser in life, who—like many self-identified depressive losers—gathers whatever minor self-esteem he finds in life from the idea that he rejects the rat race of society and has dropped out of seeking success within it. Yet, also like many depressive losers, he still longs for the rewards of the very status game he hates—including the sexual rewards—and envies the men who win the status game, while at the same time hating himself for this longing.

Frederick regularly glances through articles in newspaper entertainment sections about attractive young female starlets. After tossing out the main news sections, which are filled with the “record of yesterday’s monstrous deceptions, betrayals, and obscenities,” he flips through the starlet articles, “staring, lengthily and gloomily, at the accompanying pictures.” He observes: “Invariably the girls were scantily clad, posed in such a way as to show to advantage the highlights of preposterously lovely bodies, and always one photo showed a close-up of their luscious mouths puckered suggestively, round and hot and soft and ready for erotic oral business.”

Yet, at the same time as he longs for these women, he sees them as superficial prizes for a superficial societal status game. He simultaneously hates the game itself, and the fact that he’s losing it: “I would never have [these women], knowing that they were rewards—like a Rolls-Royce—for those obedient men who accepted society’s standards of success, standards that seemed to me not only wrongheaded but grotesque.” (pp. 15-16)

Not a pleasant character—but unfortunately I saw some of myself and my inner struggles in him.

In many cases, Dawkins argues, the way genes best selfishly replicate is by coding for cooperation among the organisms that contain the genes. But, Dawkins argues, such cooperation among organisms still serves the selfish ends of the genes’ replication; if the genes are better replicated by coding for violence rather than cooperation in some evolutionary niche, they will code for that. (And, I would add, cooperation and violence are often two sides of the same coin: a great deal of human cooperation involves cooperating to inflict violence on or in some other way aggressively compete against other groups of humans, who are themselves cooperating to do the same in reverse.) The point is, genes themselves are amoral replicators, even if the organisms they code for sometimes display consistent and deeply-held morality.

Most of the “insights” that came this way were worthless. But one day, I did get one of these ideas during a meditation, leapt off my bed to my computer microphone and recorded a meditation, which many people later did tell me was helpful to them. It was called “Loving the Unlovable Within.”