In the fall of my freshman year at college, in 1995, Playboy magazine sent a glimmering tour bus to our New England liberal arts campus to promote its recently-published “Women of the Ivy League” issue.

The only time in my life that I have been possessed by an all-encompassing, rigid, demagogic ideology coincided with Playboy’s visit to my school. My ideology did not think kindly of Playboy.

For reasons related to militant teenage ethical veganism, and from the influence of a beloved English teacher, since my junior year of high school, I had been a hard-core adherent of ecofeminism. This theory, which emerged from the radical environmental and radical feminist movements in the seventies, held that male violence towards women and human violence towards animals and the environment stem from the same source: how men within patriarchy objectify everything around them for their use, including women, non-human animals, colonized peoples, and entire ecosystems.

In ecofeminist theory, pornographers were a central misogynistic oppressor. In her book Pornography and Silence: Culture’s Revenge Against Nature, Susan Griffin argues that, counterintuitively—”the metaphysics of Christianity and the metaphysics of pornography are the same.” In her view, both the pornographer and the Christian theologian hate women’s bodies and treat women as the “other,” and dominate and punish women’s bodies through their worldviews and sexist practices.

I had devoured Pornography and Silence in high school, along with a whole reading list of other central ecofeminist texts, including Woman and Nature: The Roaring Within Her, also by Susan Griffin, The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology and the Scientific Revolution by Carolyn Merchant, and The Rape of the Wild: Man’s Violence Against Animals and the Earth by Andrée Collard with Joyce Contrucci. I had also read a wide swath of radical feminism in general, particularly Andrea Dworkin, who was not necessarily an ecofeminist but who was among the most militant writers who ever took up pen against porn.

I was into some obscure stuff for a teenage guy. For example, did you know that there was a field called feminist-vegetarian critical theory? As a militant vegan sixteen-year-old ecofeminist, not only did I know about it, but—from reading a book called The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory by Carol J. Adams—it was my religion.

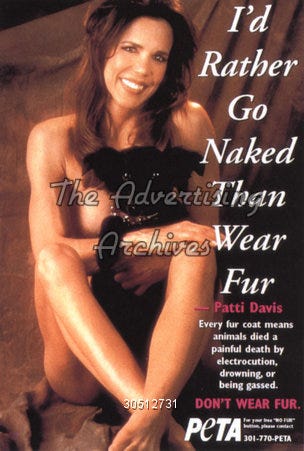

In a niche newsletter to which I subscribed, Feminists for Animal Rights, I had read Adams critiquing a recent advocacy advertisement by PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) featuring Patti Davis (Ronald Reagan’s daughter, who had recently posed nude for Playboy). In the PETA ad, Davis posed nude again; this time, she was covered only by Hugh Hefner’s poodle, which she was cradling. “I’d Rather Go Naked Than Wear Fur,” the ad headline said. This was part of an ad series that PETA had been running with that headline, featuring female celebrities in the nude, covered only by their hands, camera angles, or banners they were holding with that statement. The series had included The Go-Go’s, Christy Turlington, and Kim Basinger.

In the Fall-Winter 1994-95 issue of Feminists for Animal Rights, Adams blasted the ad:

A connection exists between the treatment of women and the treatments of animals. . . . A patriarchal epistemology responds to differences (such as race, sex, species) by labeling those who are different as “other,” and then objectifying those who are “others,” so they may be used instrumentally. Ecofeminists call this a “value hierarchy,” in which power is inscribed over others who hold less power and are therefore seen as having less value. One feminist coined the term “somatophobia” to refer to hostility to the body. In our culture, the body has less value than the mind or the soul; anyone equated with the body will also thus be unvalued or undervalued. This concept helps us recognize the relationship between different forms of oppression: those equated with bodies (like people of color, animals, and women) rather than minds or souls (like white people, humans, and men) are oppressed in our culture because of this equation with the body and with each other. . . .

It is also the same epistemological process that views women’s bodies pornographically. Pornography has been historically a way for men to institute their status as subjects by having others who have the status of objects. . . .

Given this analysis, the “I’d rather go naked than wear fur” campaign is intrinsically problematic. . . . But the added twist that occurs with the Patti Davis ad is not only in its alliance with Playboy, which has made harm to women through pornography a man’s entertainment (because it furthers women’s objectification, and reproduces sexualized domination), but the specific concern of bestiality [via Davis posing nude with Hefner’s poodle].

Thus, when Hugh Hefner sent his slimy recruiting minions to my school-town turf, ready to exploit our unsuspecting, innocent young women, I needed to defend our campus from the predations of the nation’s pornographer-in-chief.

I sat at my dorm room desk and composed a letter to the Brown Daily Herald:

I do not believe that pornography should be censored, or that Playboy should be barred from recruiting on campus. I am not of the school of feminists who fear pornography because they believe it is a major cause of violence towards women. Rather, I believe that pornography is a symptom of the basic male-dominated, male-oriented structure of our society, a structure whose inevitable outcome is violence towards women; I fear pornography for what it symbolizes.

To me, pornography symbolizes most of what male-dominated society stands for: separating “me” from “other,” while privileging the “me” and hating and subordinating the “other.” Part of this subordination means reducing the “other” to a mere object (whether it be men reducing women to fleshy receptacles for their penises, or humans reducing animals to pieces of flesh to chop up, cook, and eat).

Another aspect of our society that pornography symbolizes is how we prefer the image or abstraction of something or someone to the actual thing or person. We prefer seeing nature in a calendar to hiking through it ourselves. With the advent of the “information superhighway,” we are beginning to prefer communicating electronically to face-to-face. And, with regard to sexuality, many men prefer the image of a woman printed on paper to the woman herself.

Why? Because it’s easier. Interacting with the image or abstraction of something or someone does not demand of us the subtlety, patience, and emotional commitment that interacting with the actual thing or person does. Unfortunately, what many of us don’t realize is that subtlety, patience, and emotional commitment make most of what we do rewarding.

I clicked “send” on the letter.

This was competent, textbook ecofeminist criticism of pornography (mixed in with a bit of neo-Luddism—an adjacent ideology to which I was also partisan). The tone was demagogic, to be sure, but that certainly didn’t distinguish it from much radical political writing. The only thing remarkable about it was that this textbook ecofeminism was written by an eighteen-year-old male; the combination of my age and my sex made me an uncommon mouthpiece for radical ecofeminism.

But what I did later that afternoon laid bare both my age and my sex.

A few hours later, as was my custom most afternoons, I locked the door, and fished in my dresser for a key. I double-checked my roommate’s class schedule, taped to the wall. Then I kneeled by my bed, pulled my suitcase out from under, and unlocked it.

From within this locked treasure chest, I removed a stack of magazines: well-worn Playboy and Penthouse magazines I’d been collecting since I was thirteen, when I used to shoplift them from the local grocery store by sticking them in newspapers and then buying the newspaper without paying for the hidden porno mag.

I unbuttoned my fly and dropped my pants and underwear to my ankles. I put a towel down on my desk chair and sat on it. I began flipping through image after image of women “reduced to fleshy receptacles for my penis,” as I had written, progressively stroking myself to excitement.

After a few desperate minutes, I wiped myself with a tissue. I kicked my pants and underwear off my ankles, and wrapped a towel around me, trying to conceal what remained of my hard-on in the wrap of the towel. I put the porn mags back under lock and key. Then I walked out of my room towards the dorm showers, to cleanse myself.

In the Mental Junk Closet…

I’ve heard porn performers say, of the moralizing masses, “You point with one hand and masturbate with the other.” In this case, I typed the letter with both hands, and then wanked with one after.

I’d be lying if I said this was the only time I’ve been so hypocritical. It’s probably not even the worst instance, and certainly not the most consequential.

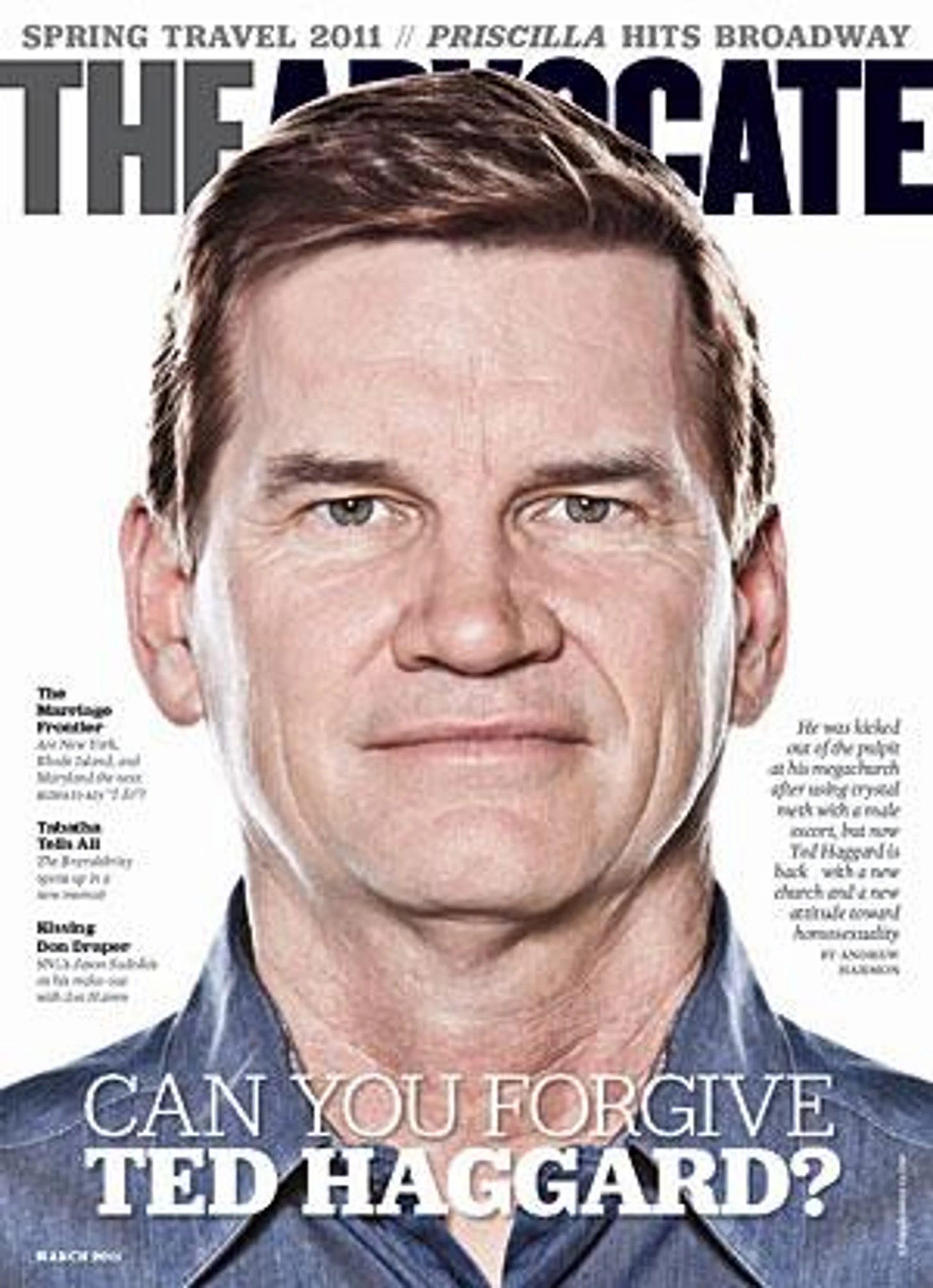

But I can’t recall another time when I was so brazenly hypocritical: expressing passionate moral demagoguery in a public forum and then violating my own demagogic morals flagrantly in private only hours later. That’s Ted Haggard-level hypocrisy.1

What motivated me to write that letter? On an ideological level, I was a true believer. Is the Christian demagogue less a believer in Christ because he masturbates? If I had been chatting up a lot of women with my ecofeminist rap, it could have been seen as a cynical ploy to get in their graces. (Feminists often say they are skeptical of male feminists. I wonder why. There’s a term for it: “macktivism,” a play on “mackin’,” which is street slang for flirting with or picking up women.)

But I was a weird, unconfident dude, hardly talking to any women, let alone feminist women; whenever I did talk about ecofeminism in class (which was frequently), I was mostly mocked, even by my female classmates; the “eco” and vegan parts, in particular, got the same eye rolls as they do now, and even more so back then, when veganism and radical environmentalism were more fringe.

I was an ecofeminism geek, and a lonely one at that—staying in my dorm on Saturday nights and reading the ecofeminist liturgy. And then… when the loneliness got unbearable… pulling out a Playboy, and my penis, for some gaiety to escape from the dreariness of my militant political consciousness.

Such splits within the self—devoting oneself intensely and earnestly to an ideology in one part of the mind, while another part of one’s mind runs wild in a contrary direction—are not easy to explain.[2]2

The only way I can explain it is that the part of the mind susceptible to ideology seeks to impose order and consistency on an unruly and inconsistent world. The challenge is that our own minds are part of what is most unruly and inconsistent in the world. It’s easier to pretend that our minds are consistent than to actually be consistent—particularly when our unruly desires conflict with a preferred moral order.

And the easiest way to pretend to be consistent is to have what amounts to a mental “junk closet”—that place where we just shove stuff that’s inconsistent with the order we are trying to impose. Then the rest of our mind seems as orderly as a home in which all the mess has been aggregated into a junk closet.

The word “hypocrisy” stems from “Attic Greek hypokrisis ’acting on the stage; pretense,’. . . [and] from hypokrinesthai ’play a part, pretend.’”

This, I think, is the root pretense of hypocrisy: play-acting to others, and to oneself, that one’s mind (and its simplistic models of the world) is more orderly and consistent than it actually is.

The problem with the “mental junk closet” approach to achieving (the appearance) of consistency in our minds is that it heightens disorder dramatically in the “junk closet” part of our minds. The stuff in the junk closet is way messier than if we just spent the time to engage with it on its own terms and sort it out. And as we stuff more and more stuff into that messy closet, eventually it bursts out, often in ways that shock ourselves and others.

A Loin Full of Ecofeminist Sin

The year after I sent my sticky-fingered letter to the Brown Daily Herald, still a militant ecofeminist in heart and mind (though with a loin full of ecofeminist sin), I was handling music at a sophomore party.

A woman walked up to me at the party and asked me about the music. I had just put in some Cuban salsa. She liked the music. She was Cuban — born in Miami, with parents from the island. Short with shoulder-length, jet-black hair, pale skin, and cherry lips. She wore a tight, black-lace dress.

She was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen. I realized, while talking with her, that I had seen her a year earlier, in a play she was in. Then, too, I had thought she was the most beautiful woman I had ever seen. I had thought about how to meet her. But when I read on the program she was a graduate student. I figured there was no way she would be interested in me given the age gap, even aside from her pedestal-worthy looks.

But here I was, talking with her. I don’t think I had ever said more than five words to a woman this beautiful.

She sipped her sangria. “This stuff is disgusting.”

I declined to tell her that I had made it. “There’s some nice wine in the pantry,” I said. We walked over. The bottles were empty. “I have some Cuban rum down in my room.”

Her eyes lit up. “I’ll trade you some speed for it.”

“No, no, that’s okay.”

“How old are you?” she asked on the way down.

“Nineteen,” I said. She shot me a nasty glare. “How old are you?” I asked.

“Twenty-five.”

“Do You Want to Be the Man She Tells Her Deep Dark Secrets To,

or Do You Want to Be Her Deep Dark Secret?”

At that time, my view of the correct male gender role was the “sensitive male”—the open, friendly, supportive guy who shares hugs and tears with his female friends. I’d finally made some female friends, though they were not ecofeminists (nobody was an ecofeminist). I did not go out and try to “score,” because I viewed it as an expression of predatory male sexuality in a patriarchal culture. I viewed dating as a superficial preoccupation of those who did not understand the urgent attention the environmental crisis needed.

Because ecofeminism posited psychological roots (the ideology of patriarchy) to the problems it addressed, it also posited psychological solutions. The key to undermining patriarchy, according to ecofeminism, was undermining the patriarchal thought structures within our minds. If I walked down the street and felt sexual desire for a woman, I felt guilty. After all, I didn’t even know her. Therefore, my gaze clearly reduced her to a mindless body, an object for my male sexual consumption. I felt that if I eradicated this and other patriarchal thought structures within my mind, I would contribute to the eventual downfall of patriarchy. It was psycho-therapeutic guerrilla warfare.

These were unusual views for a teenage guy, and people often wondered how I came to them. The lineage went something like this:

When I was fifteen, my father—an antiwar activist—became vegetarian for ethical reasons, related to his philosophy of nonviolence. Like many people encountering ethical vegetarianism for the first time, I thought his decision was one of the nuttiest things I’d ever heard; my favorite meal at the time was roast beef, medium rare, without a vegetable in sight.

I decided to read a book about it, to see what had gotten into his head. My father had a copy of Diet for a New America by John Robbins on his shelf. I picked it up and started reading it. After a few hours of reading grisly details—and, even more persuasively, seeing grisly images—of cows, pigs, and chickens being tortured in modern factory farms, I decided to convert to vegetarianism myself. (I later learned that, in the vegetarian world, Diet for a New America is widely considered the book that has converted more people to vegetarianism than any other; Animal Liberation by Peter Singer is another contender.)

Within a year, I was a hard-core ethical vegan. Something that is difficult to understand unless you have been a hard-core ethical vegan is how alienated you feel from most of the human population, who are meat eaters. If you literally believe that intentionally killing animals is murder—I wore a t-shirt that said, “Meat is Murder,” and I meant it—then by definition you believe that many of your friends, family members, and in fact most of the fellow members of your species, are ethically equivalent to murderers.

Demagoguery can be defined as leadership and communication that presents issues in stark, simplified emotional contrasts, with “us” as the side of all that is right, good, and enlightened, and “them” as the side of all that is wrong, evil, shadowy, and dark. I became a demagogue for ethical veganism. (I’m sure you’ve encountered the type.)

During my junior year of high school in 1993, before I was on the Internet and before I knew of Godwin’s Law of Nazi Analogies—”as an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches one”—I confirmed Godwin’s Law in the finals of a class-wide oratory contest. After tying meat eating to global starvation (given how much grain is fed to livestock and how many more people could be fed on a vegetarian diet) and the ecological devastation of the rainforests, and after explaining how billions of animals are tortured in factory farms, I stunned the audience, my entire school, with this accusation:

You have a strong incentive to keep yourself ignorant of the true, full impact of your meat consumption, because if you did know the true, full impact, but chose to continue eating a diet that is directly related to the unimaginable suffering of billions of animals, to the destruction of our world’s most vital resources, to the starvation and death of more than sixty million human beings every year, then I ask you: what would distinguish your morality from a that of a mass murderer or a Good German?

If you view the world in these terms, it’s simply too much to consider that so many people would commit such atrocities knowingly; it makes you go crazy. So you start searching for answers. How do so many humans become desensitized to the violence they are committing?

This is when I got into ecofeminism. A beloved high school English teacher of mine, whom I’ll call Mr. Hargrove—and whom I still consider by far the greatest teacher I ever had in my entire run of formal education—handed me The Sexual Politics of Meat. He was a radical environmentalist, ethical vegan, and ecofeminist, who had written his master’s dissertation on the connections between hunting and pornography. But—like all great teachers—he didn’t try to persuade me of anything. Rather, he curated a stellar personalized reading list for me of texts he thought would blow my mind, given the existential questions around which my soul was burning.3

And blow my mind it did. There’s a wide literature on “conversion” experiences. I had a full-on conversion experience to ecofeminism, particularly from The Sexual Politics of Meat. All the sudden, everything made “sense” to me. It had seemed completely senseless how so many people could inflict so much suffering on so many sentient beings. Now I had a simple explanation: male objectification of “the other.”

This is why adherents to an ideology—and I think we’re all adherents to one ideology or another—are so passionate about defending it. It’s a life raft of (apparent) sense in a senseless world. Senselessness feels like insanity, like being enveloped by the battering waves and drowning. We cling to ideology to keep us from going insane. (Even though it is precisely our ideology that makes us look insane to those with opposing ideologies. We’re all crazy to somebody.)

The particular “sense” that ecofeminism gave me—the explanation it gave me for why the world seemed so fucked up to me—centered around the concept of objectification: reducing beings that have their own subjectivity into objects for use and consumption. While of course all schools of feminism are concerned with male objectification of women (the “male gaze,”) ecofeminism extends the analysis, arguing that objectification is the central organizing principle of patriarchy, and that it pervades patriarchal men’s relationship not just to women, but to everyone and everything that isn’t them, including colonized peoples, non-human animals, and Mother Nature herself.

All of this gave me, at last, a unitary explanation for all the fucked-upness I saw in the world—the warmongering, class divisions, human destruction of nature and violence towards animals. And it gave me hope for a way out for our species and all species. All our shit stemmed from this one root evil: objectification. Get rid of that evil, and you get rid of all the other evil. Simple!4

Or, not so simple: because I was an extremely horny teenage dude. For those who have never had the amount of newly surging testosterone running through them that a typical adolescent male has (in this case, a straight male), it may be difficult to adequately convey how desperate and intense the craving for female flesh can be. Of course, most teenage guys crave romantic love too; adolescent boys can be just as emo as adolescent girls. But on some level, the unrelenting, non-stop, overwhelming craving is just for fucking flesh—good ol’ objectified T&A. Anything that moves, and is adequately attractive. Testosterone is a strong drug; it focuses the mind. Especially when your growing body is first starting to inject the drug into your virgin veins.

So that’s where I was: a split being. The controlling part of my mind (what Freud would call the superego) had concluded, through some precocious political reading seeking answers about evil, that objectification was the source of all evil, and that objectifying animals for meat, and women for sexual meat, was evil. The uncontrolled, wild part of my mind (what Freud would call the id) craved my pound of female flesh. And if I couldn’t get it (and generally I couldn’t, being such a strange dork), then I would settle for pounding—and pounding and pounding—a six-inch piece of my own flesh. All while desperately flipping through pages of women reduced to two-dimensional images of flesh. Which would satiate my hunger for a few hours. Until the hunger came back, and the battle between superego and id would begin anew.5

I desperately wanted a girlfriend. Stuffing this ugly id-battle in my mental junk closet, I thought that if I was a kind, sincere, supportive male, one who did not “play the game,” I would find a woman who would want a relationship with me.

That never happened. By sophomore year, I had several girl friends, but nowhere remotely in sight was a girlfriend. I once saw an ad for cologne in Esquire, which read, “Do you want to be the man she tells her deep dark secrets to, or do you want to be her deep dark secret?” I was definitely the man to whom she told her deep dark secrets.

My female friends would complain to me about how “Men are such assholes.” Then they would describe how one such “asshole” had just thrown them on the bed and fucked just how they wanted and needed to be fucked. “Why don’t they ever go for nice, caring guys like me?” I wondered after being passed over in favor of yet another macho clod.6

I wanted sex desperately, yet I felt guilty about this desire.7

*****

All this was running through my head as Juana and I walked down my dorm hallway. Once we got to my room, Juana sat down on my bed. I discovered she was not just any old grad student, but a third-year Ph.D. student—lit theory in the English department. This added to my nervousness. The phone rang. It was my friend Kate. I forgot that we were supposed to hang out that night. Fuck! I didn’t know what to say. If I told Kate I couldn’t hang out with her, I would have to explain why, which would be a thorny path with Juana sitting right there.

“Yeah, I’m hanging out with a friend, drinking, listening to music. Wanna come over?”

Juana looked at me as though I had just pulled out a Parcheesi board. Kate knocked on the door. We sat around, drinking Cuba Libres. After a while, Juana had to go. I gave her my phone number. She folded it, put it in her purse, and then wrote her number down and handed it to me.

*****

“There’s something about the word fuck that just isn’t okay,” Richard said. “It has this tone of violence.” Richard was a fellow student of Mr. Hargrove, the English teacher who had turned me onto ecofeminism in high school. He was my sole comrade in ecofeminism. I had used the word “fuck” in some sentence during one of our epic ecofeminist discussions. Richard told me he didn’t like me using that word.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Well, look how it’s used. When a guy says, ‘oh yeah, I fucked her,’ there’s this element of conquest, of subduing the feminine body.”

“Look, there’s a lot to be said for tender lovemaking,” I said. But sometimes you just wanna fuck.”

“There’s nothing wrong with that kind of sex,” Richard said. “But something about the word—it just adds this tone of rape to it.”

“But if she wants to fuck—how can it be rape?”

“I’m not saying that ‘fucking’ is rape. I’m saying that the word itself has subtle connotations of rape. I think I read somewhere that in some hunting-gathering languages, the word that functions for them like ‘fuck’ is also the word for ‘to hunt.’ When you use the word, you just perpetuate the connotation. The more you use it, the more you contribute to that element of male violence in our culture.”

“But word meanings can change,” I said. “No one means ‘to hunt’ anymore. They just mean... to fuck.”

“I’m just saying that the word itself has unhealthy connotations,” Richard said, “and I don’t think you should use it so much.”

I couldn’t believe it. How many nineteen-year-old males had engaged in serious discussions about the appropriateness of using the word “fuck” in light of its perpetuation of patriarchal gender relations? For that matter, how many nineteen-year-old females had engaged in such discussions? I felt like something was out of place. “I think we’re not acting like regular nineteen-year-old guys.”

“Well, if we really want to act like regular nineteen-year-old guys,” Richard said, “we can go out and get drunk and get laid and give up on activism altogether.” I saw what he was saying. But something seemed wrong about erasing words from my vocabulary just because they had subtle etymological associations with the dominant culture Richard and I despised so much.

I guess I already did that. I never joked around with the n-word. But “to fuck” doesn’t have all the immediate negative connotations of the n-word. It just connotes aggressive sex. Connotation is based in use, I tried to convince Richard. Do my political values have to be reflected in every aspect of my daily life, in my every word? Richar would say yes—anything less would be hypocritical.

Later in the discussion, Richard expressed to me his guilt about liking Led Zeppelin. “I mean, I like the music, but it’s so violent. It’s definitely part of the culture we’re trying to change. I’m sure Mr. Hargrove doesn’t listen to it. I doubt he even wants to.”

At this point, I asked myself: “Does my political orientation need to be reflected in what kind of music I listen to?” My politics suddenly seemed totalitarian to me, or more accurately, puritanical: the need for everything to be politically productive, the guilt and self-loathing at pleasure for pleasure’s sake. It was like Stalin’s state-condoned “Socialist Realism” painting style: facile, didactic, and easily comprehended, always with a readily grasped moral, usually concerning the virtue of the proletariat and the glory of the cooperation. It was some of the worst painting in the history of art.

“Fuck this,” I thought. Those two words were the first time I fully admitted to myself that my ecofeminism, at least the way I was holding it, wasn’t working for me. It was the first time I admitted to myself that there were parts of me I could no longer repress.

*****

I’m six years younger than her. . . She could get any guy she wanted in the world. . . Why would she be interested in me?... But, she was flirting with me; I’m sure that was flirting... And she did give me her number...

“Hi, Juana?”

“Yes.”

“This is Michael Ellsberg.”

“Oh, hi, how are you?”

“Fine, thanks. Listen, I’m going to this rave thingy downtown on Friday night. It’s at a club called Generation X. I’ve never been but it’s supposed to be good. Would you like to join me?”

“I’ll pick you up at eleven.”

Kids dancing to house music filled the club. Thump thump thump thumpthumpthump. We walked onto the floor. She wore a short-cut white cotton dress that draped lightly over her body; it looked more like a nightie than a dress.

She was, as far as I could tell, the most gorgeous woman in the room. All the men eyed her. For the first time in my life, I felt envied. She bumped into a few female friends. We all danced together in a circle. Juana grabbed one of these women and started dancing with her closely. Soon they were grasping each other, rubbing together, practically making love on the dance floor. Thump thump thump thumpthumpthump. The two disentangled, and the woman and her friend sauntered off.

“THAT GIRL HAS A CRUSH ON ME,” Juana yelled into my ear.

It was time to make my move. I knew from middle school that the only time neuro-impulses sent by the brain did not translate into movement in an appendage was when the brain was ordering a guy’s arm to go around a girl for the first time, or to hold her hand. You felt the brain commanding the movement, but the hand just sat there, limp. So, I did what I used to do in middle school: one, two, three, four, FIVE! I reached over and grabbed her hand. She pulled close to me. I placed my hand on the small of her back. She wrapped her arms around me. I felt her chest press into mine. I leaned down and sniffed her freshly washed hair.

She stood up and leaned into my ear. “LET’S GET SOMETHING TO DRINK.” She grabbed my hand and marched into the other room. Surely every man in the room was thinking, “What’s a girl like that doing with a guy like that?” I tried to play cool, as if I hung out with women like Juana all the time.

She ordered us two vodka tonics. We sat down on a couch in the corner. She grabbed an ice cube out of my glass and started tracing it on my face. I leaned forward and kissed her. She kissed back.

Kissing turned to a full-on make-out. Thump thump thump thumpthumpthump. The people standing around us with their drinks and cigarettes eyed us. At parties I’ve attended, whenever a couple sat lip-locked in a corner, people made nervous little comments such as “Well, they’re getting started early,” or “I guess they hit it off.” For the first time in my life, I was that person in the corner. It felt great.

“Shall we leave?” I asked.

She drove a black sports car. She zoomed past where the quaint colonial part of town faded into dreary industrialism. We stepped into her apartment. White walls, framed prints, bare hardwood floors. Bookcases full of literary theory and contemporary art novels.

She showed me around. She poured us some wine. She grabbed a pint of strawberry ice cream from the freezer. She sat us down on her couch, and started playing Star Wars on her VHS. We fed each other ice cream and drank wine as we watched the opening sequence. Soon we were feeding each other the cream with our mouths. I shut the off the TV.

“Shall we go to my room?” she asked. I stood up and started picking up our things.

“Don’t worry about it,” she said She led me to her room. We kissed in the middle of it. I turned off the light. We collapsed onto each other on her bed, and the night began.

*****

I had a date with Juana the night after Halloween, for a costume party. She planned to go as a dominatrix. I didn’t have a costume, so I put on all my retro seventies clothes at once; I looked like a wannabe pool shark. When Juana arrived, she wore a black skirt, black boots, and a black rubber overcoat. It looked more like her normal outfit than a costume.

When we arrived at the party, I discovered that the outer layer was not her costume. She pulled her dress over her head, revealing a black rubber G-string, a black lace bra, and a flogger. We met her friend, Marta, who wore a black rubber miniskirt, and Marta’s tall boyfriend, Ortíz, with black leather pants, a bare hairy chest, and a spiked dog collar, connected to Marta with a leash. We all danced for a while, and everyone was watching us. I tried to keep my cool and feign confidence, as if I went to SM orgies all the time.

The costume contest started. The contestants included a man with a shower head and shower curtain, a Brady Bunch group, and a Thor impersonator. And Juana, Marta, and Ortíz. They pushed into the center of the crowd. Ortíz dropped to the floor. Marta pulled his leash. He whimpered like a stuck puppy. She whipped him. He dog-slobbered up her legs. She whipped him again. Juana whipped Marta. They congregated into a pile of whips and chains and orgiastic yelps on the floor in the middle of the room.

Most of the crowd consisted of stressed-out grad students in their standard grad-student tweeds. They clutched their glasses of Chardonnay apprehensively.

“Those aren’t grad students like I know!” a thin tweedy man next to me exclaimed to his friend.

After the contest, which they didn’t win for some reason, Marta and Ortíz went their way, and Juana and I returned to her apartment.

*****

On Friday nights, Juana and I would go out somewhere, then go back to her place and stay up most of the night fucking, sleep in until late brunch hour, eat something, then spend the afternoon in bed fucking more.

We never went out on Saturdays. She reserved Saturday nights for going out and “picking people up,” as she put it.

Once, she showed me her closet. It overflowed with whips, chains, leather and rubber outfits, and other bondage supplies. This was fifteen years before Fifty Shades of Grey put BDSM in the national spotlight; it was still a fringe subculture in the mid-nineties. To meet someone with a closet like that was, for me, extremely exotic, and—to my ecofeminist sensibility—scary.

The only thing I knew about BDSM—or sadomasochism or SM, as it was commonly called back then—was what I had read from radical anti-porn feminists. The radical feminist line on sadomasochism was that it represented a form of extreme internalization of the hierarchical relations of patriarchy, so that individuals living within patriarchy came to enjoy being dominated and controlled, and to experience it as sexually exciting.

For example, here’s Andrea Dworkin, the radical feminist, and anti-porn firebrand, in a 1975 speech I had read in Our Blood, an anthology of her speeches:

Within the confines of the male-positive system. . . . [f]ucking is entirely a male act designed to affirm the reality and power of the phallus, of masculinity. For women, the pleasure in being fucked is the masochistic pleasure of experiencing self-negation. Under the male-positive system, the masochistic pleasure of self-negation is both mythicized and mystified in order to compel women to believe that we experience fulfillment in selflessness, pleasure in pain, validation in self-sacrifice, femininity in submission to masculinity. Trained from birth to conform to the requirements of this peculiar worldview, punished severely when we do not learn masochistic submission well enough, entirely encapsulated inside the boundaries of the male-positive system, few women ever experience themselves as real in and of themselves. . . .

I believe that freedom for women must begin in the repudiation of our own masochism. I believe that we must destroy in ourselves the drive to masochism at its sexual roots. . . . I believe that ridding ourselves of our own deeply entrenched masochism, which takes so many tortured forms, is the first priority; it is the first deadly blow that we can strike against systematized male dominance. In effect, when we succeed in excising masochism from our own personalities and constitutions, we will be cutting the male lifeline to power over and against us, to male worth in contradistinction to female degradation, to male identity posited on brutally enforced female negativity—we will be cutting the male lifeline to manhood itself. Only when manhood is dead—and it will perish when ravaged femininity no longer sustains it—only then will we know what it is to be free.

And yet, when you’re a teenage ecofeminist boy, and the most beautiful woman you’ve ever seen stands by her closet full of fetish and bondage gear, and asks you to put a nipple clamp on her… are you going to tell her no because Mommy Dworkin would tsk tsk?

I felt nervous putting the nipple clamp on Juana. I didn’t want to hurt her. So Juana suggested I try it on myself first. “It’s really not that intense. Give it a shot,” she said. I put it on the weakest notch. I winced and took it off.

“This is not too intense?” I asked. “You really want this?”

Juana held out one of her perfect, large natural breasts towards me. “Right here,” she said, pointing at her nipple.

I did as she said.

“Clamp it all the way down, hard” Juana ordered.

I took a deep breath and clamped it. Her eyes went to the back of her head, and she let out a sigh. She laid back on her bed. We fucked for a few minutes while she was consumed by the pain-pleasure. But the idea of a woman asking me to inflict pain on her while we fucked felt weird, and wasn’t a turn-on for me. “Why would an empowered, feminist woman possibly want this?” I wondered to myself, as I was half-heartedly pumping her. Juana could tell my heart wasn’t in it. I was not an effective sexual Dominant. (I didn’t even know what a sexual Dominant was.) Rather, I was bewildered. Juana took the nipple clamp off, and we stopped fucked.

“Sex without pain is okay,” she said, “but to really enjoy it, I need pain.” I felt hurt and confused by this. Before this afternoon, she seemed to have been enjoying our sex, and I wasn’t inflicting pain on her. Wasn’t my “kind, gentle, ecofeminist” sex good enough for her?

According to the feminist theorists I was reading at the time, when a woman was attracted to a stereotypically dominant man, it was simply a failure on her part to understand her political conditioning, a mistake that would be remedied after the feminist revolution. As Gloria Steinem wrote in her 1983 memoir Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions, this mistake on women’s part stems from

a refusal to differentiate between what may be true for them now, and what may be desirable in the future. For example, a woman may be attracted only to men who are taller, heavier, and older than she, but still understand that such superficial restrictions on the men she loves and enjoys going to bed with won’t exist in a more free and less-stereotyped future.

Steinem’s analysis gave me, a man of exactly average height (5’9”) and average build, and less-than-average proclivity towards sexual confidence or bravado, hope for the future. Maybe there was a sexual place for me after the ecofeminist revolution?

In her master-tome Intercourse, Andrea Dworkin presented the one kind of heterosexual sex that she felt had the potential to be non-violent, approved, and “humane” from a radical feminist perspective. Dworkin writes:

Shere Hite has suggested an intercourse in which “thrusting would not be considered as necessary as it now is . . . [There might be] more a mutual lying together in pleasure, penis-in-vagina, vagina-covering-penis, with female orgasm providing much of the stimulation necessary for male orgasm.”

These visions of a humane sensuality based in equality are in the aspirations of women. . . .

Needless to say, this sort of “humane sensuality” was not the aspiration of Juana, who (as only my second sexual partner in my life so far) comprised fifty percent of my sample size.

When finally in the presence of a flesh-and-blood woman, with flesh-and-blood desires—not the abstract womanhood I was studying in my feminist textbooks—I was baffled and confused; Dworkin had steered me wrong. Juana’s interest in this type of “humane” feminist sex, in which the man is totally gentle and passive, ranked right up there with her interest in a night of bingo at the nursing home.

Juana’s passion for being on the receiving end of pain and domination during sex was a glitch in my anti-porn ecofeminist matrix; according to that matrix, only a woman completely controlled by the patriarchy would be sexually aroused by a man inflicting pain on her. And Juana definitely did not seem to be controlled by the patriarchy—or by anything or anyone else. Certainly not by me—a sexually-inexperienced sophomore male vegan ecofeminist.

*****

“I’ve been thinking. I don’t want to see you anymore,” Juana said. It was the Thursday after Thanksgiving break. I had called to make plans for that weekend.

“What?”

“I don’t want to see you anymore.”

“Why not?”

“You’re too young for me.”

“We don’t need to go out in public...”

“It’s not that. It’s just that... I want someone more experienced. I need someone darker. And you need someone lighter.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“I want someone who wears black, who’s into SM. I feel like I always have to be so positive around you. Like your veganism. I just don’t give a fuck about that shit. I really don’t.”

“Can we at least meet and talk about it?”

“Look, I don’t want to see you again, OK?”

“But…”

“I hope I didn’t hurt you.” Click.

We had seen each other eight times. Our month-long relationship had been completely meaningless and politically incorrect. The only reason I saw her was that she was gorgeous and willing to see me. The only reason she saw me was that I was young and she called the shots. There was no emotional attachment at all, no love. Just mindless pleasure.

It had been the happiest month of my life.

Diamanda & Domination

Diamanda Galás, vocalist and pianist, was giving a solo concert in town, a few months after Juana dumped me. I was drawn to the concert from her picture on the poster: jet-black hair with dangerous eyes. She reminded me of Juana. One of the review snippets called this live performance of her new work Schrei X “the most harrowing experience in a lifetime of concert-going.” That word, “harrowing,” reminded me of Juana. Everything goth and darkly beautiful reminded me of Juana.

I missed Juana like crazy. I’d left her a few messages over the months, asking if she’d reconsider me; she never returned the messages, so I gave up. Seeing the poster for Diamanda, I wished I could have brought Juana to this show on a date. I had seen Juana around campus a few times, but she either didn’t notice me or acted like I didn’t exist. I decided to go to the concert alone, just to bring back memories of that exalted month with Juana. Nothing like that month had ever happened to me.

At the show, a sole piano and microphone set the stage. The lights dimmed. The room was pitch black except for a small light on the music stand. A tall, slim figure in a long black dress walked out. Applause. She stood in front of the microphone, silent for at least a minute. Then, from the speakers emanated the most spine-shattering, unrelenting shriek I had ever heard. About fifteen people stood up and exited the auditorium upon hearing this single note.

Amidst cries and shrieks, Galás belched out guttural sentences and spoke demonic verses in a low raspy voice. More shrieks and cries and echoes. Then, fragmentary shouts of violent dialogues, perhaps self-dialogues in her mind: “Cunt! Cunt!“ Then she dove into what sounded like passages from the biblical liturgy in Latin, mumbling in the tone of Catholic priests.

I read during the intermission that Galás had been institutionalized at one point. Her brother, a gay man, had died of AIDS at the height of the crisis in 1984, and in 1989 she had been arrested in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York in an early ACT-UP “die-in” protesting the Catholic Church’s stance against AIDS education.

Not long after that action, she had somehow finagled permission to perform and record her protest work Plague Mass live inside the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York—a performance the Catholic Church immediately denounced as blasphemy.8

The music was dark, but I found her cacophony beautiful. Not as in “the opposite of ugly;” the music was extremely ugly. Beautiful in that it was perfect—perfectly dark.

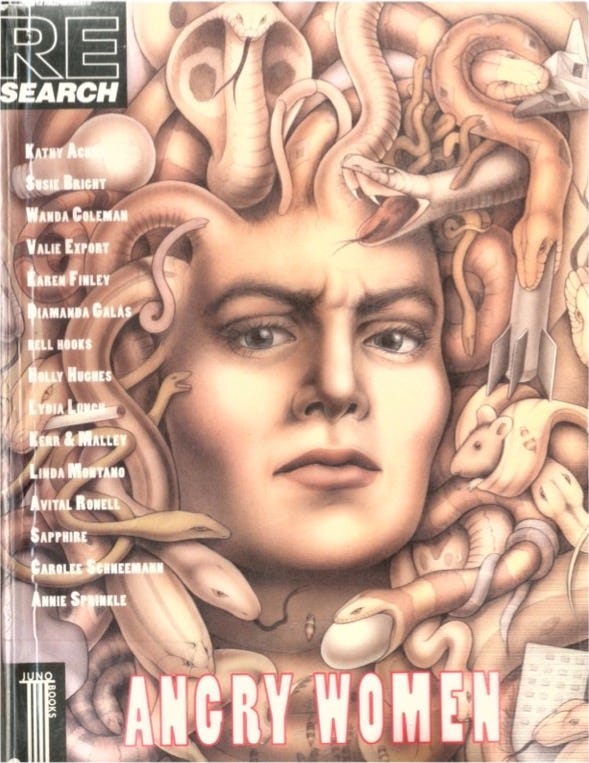

I read up on Galás after the show. I found an interview of her in a 1992 feminist anthology entitled Angry Women, edited by Andrea Juno and V. Vale. Until I read Angry Women, I didn’t know that there was a school of feminism that was harshly critical of the anti-porn and anti-BDSM feminism I had been immersing myself in for three years. This school of feminism, which started in the 1980s, called itself “sex-positive” feminism, and contrasted itself with what it called the “sex-negative” feminism of Andrea Dworkin, Catherine MacKinnon, and other anti-porn, anti-BDSM, and anti-sex-work feminist crusaders.

Up until that moment, I thought that feminism was anti-porn and anti-BDSM, and that to express approval of either was inherently anti-feminist. Given that viewpoint, my eyes popped when I started reading the interview with Galás, who ceded to no one in the stark militancy of her feminism, but who seemed to hail from a different planet than any feminist I had ever come across: Galás recounted to the interviewers:

On San Pablo Avenue in Oakland, California I worked as a prostitute for a while under the name “Miss Zina”. . . . [P]art of the reason I became a prostitute was because I wanted to be able to walk down the street in the worst fucking part of town and carry a fucking knife and know that it was my street, our street, not their street. You know that the whole streetwalker “thing” is: stealing money from tricks—that’s what you do. . . .

Basically you’d get into the car and start turning the trick and then steal their wallet and stick ‘em up. Some pimps tried to round me up and put me in their cars, but I had my life defended by these great black drag queens. These toothless bitches with knives would say to the pimps, “I’ll cut your fucking dick off—just don’t touch this thing!” I learned a lot about being a woman from these black drag queens--the power behind the role, and how you can use it. Very important—I learned how to walk down the street without fear.

Let’s just say this is not how the feminists I was reading talked. Furthermore, they had painted sex workers—or “prostituted women,” as the anti-sex-work feminists called them, disparagingly—as passive dupes who were so severely traumatized by their work that they could not exert even the most minimal boundaries towards men. This was a constant theme in anti-sex-work feminism: that men exerted absolute power and control over sex workers using them like ragdolls however they pleased, and that sex workers had no power whatsoever in relation to men.

Galás’s account contradicted this blanket characterization. While I can’t condone robbing people at knifepoint, the manner in which Galás owned the streets—and used her sexuality to do so—doesn’t exactly sound like her being a weak, passive, boundaryless ragdoll, as anti-sex-work feminists characterized all so-called “prostituted women;” on the contrary, she sounded fierce, like someone you do not want to fuck with. Reading her words, I felt my theoretical edifice beginning to crumble.

Another major fault line in my cracking theoretical edifice was BDSM. According to anti-porn feminism, fantasies of violent sex, and desires for rough and aggressive sex, were a purely male phenomenon, which men forced on unwitting, passive, controlled female sexual partners, who only went along with it because they were powerless in the situation. Without any personal experience, I adopted this view.

In contrast, here’s Galás:

There’ve been a lot of military men in my life—I like them to be fighters, at least on a physical level. There’ve been ex-cons—I like violent men; I like the idea that I can terrorize them and they can take it. I don’t want ‘em to knock me across the room unless I hit them first—and can hit ‘em back. In the area of violence and sex, I always warn people. For example, if they want to be bitten, I say, “Either you want to be bitten or you don’t, because I might lose control--there will be no halfway measures!” [laughs] And this is a domain that people who worry about being politically correct don’t address: the realm of exciting, even violent sex between consenting adults. Most people think that sex should be gentle and peaceful. But if sex is merely gentle and peaceful, I’m not even interested. Of course, when I say violence I mean “play violence” (a topic of discussion in itself)—I’m really not interested in ending up with a broken jaw or collarbone.

I like the man I’m seeing now because he’ll say, “You filthy fuckin’ white whore, that’s all you want, you piece o’ shit!” and I’ll say, “Listen, you black motherfucker, I’m gonna take you by a chain and lead you through the streets!” This is the way we like to talk to each other—any way we damn well please! Not with this wimpy, politically correct “discourse” [sarcastically]9

Whenever a political ideology advances a rigid, black-and-white stance that “X activity is oppressive to Y group,” true believers have a difficult time with the apparent counterexample of those in Y group who say they love X or who even devote a large part of their life to X.

To maintain the absolute inerrancy of their stance, in the face of such counterexamples, the next move for the true believer is to adopt some version of a theory of “false consciousness.”

Karl Marx’s intellectual collaborator Friedrich Engels coined this term in an 1893 letter. Marxists later developed this concept to explain why members of the working class are often hostile to revolutionary theory and seem to identify with the very capitalists that Marxists say are their oppressors.

Radical feminists later developed this into a theory explaining why most heterosexual women reject the revolutionary praxis of radical feminism and instead bond with—that is, fall in love with and want to have sex with—members of the male class that oppresses them.10

While not employing the term itself, in her infamous book Intercourse, in a chapter entitled “Occupation/Collaboration,” Andrea Dworkin presents the most extreme and radical theory of false consciousness I’ve ever encountered. Astonishingly, she characterizes heterosexual women who fall in love with and willingly sleep with men as “collaborators” in their own colonization and genocide:

There is no analogue anywhere among subordinated groups of people to this experience of being made for intercourse: for penetration, entry, occupation. There is no analogue in occupied countries or in dominated races or in imprisoned dissidents or in colonialized cultures or in the submission of children to adults or in the atrocities that have marked the twentieth century ranging from Auschwitz to the Gulag. [Author’s note: Godwin alert!] There is nothing exactly the same, and this is not because the political invasion and significance of intercourse is banal up against these other hierarchies and brutalities. Intercourse is a particular reality for women as an inferior class; and it has in it, as part of it, violation of boundaries, taking over, occupation, destruction of privacy, all of which are construed to be normal and also fundamental to continuing human existence. . .

[I]t is a gross indignity to suggest that when her collaboration is complete—unselfconscious because there is no self and no consciousness left—she is free to have freedom in intercourse. When those who dominate you get you to take the initiative in your own human destruction, you have lost more than any oppressed people yet has ever gotten back. Whatever intercourse is, it is not freedom; and if it cannot exist without objectification, it never will be. Instead occupied women will be collaborators, more base in their collaboration than other collaborators have ever been: experiencing pleasure in their own inferiority; calling intercourse freedom. It is a tragedy beyond the power of language to convey when what has been imposed on women by force becomes a standard of freedom for women: and all the women say it is so.

This is what Dworkin and other radical feminists thought about vanilla heterosexual women—women who just like to get fucked after a Saturday night date, just with cock alone, no whips or chains. So imagine their disdain for women who willfully sought out the whips and chains in addition to the cock!

Contemporaneous with Dworkin’s critique of women who willingly participate in patriarchal sex relations as “collaborators,” Julie Burchill wrote in her 1986 book Damaged Gods: “When the sex war is won prostitutes should be shot as collaborators for their terrible betrayal of all women.” (p. 9)

I doubt Dworkin would have agreed with this sentiment, but this kind of contempt towards willing sex workers (if not the call for revenge violence) seems implicit in Dworkin’s demagogic characterization of women who willingly have sex men as “collaborators” with patriarchy: after all, what revolutionary theory worth its salt would call for anything other than violence towards “collaborators”?

There’s a concept called “adding epicycles,” which means, adding more and more complex twists and turns to one’s preferred theory, in an ad hoc manner, in order to save the theory from counterexamples.

Radical feminists added a bunch of epicycles in their theories to account for the fact that, in the BDSM subculture, it’s not just men who dominate and women who submit; the reverse is just as common if not more so. This would seem to contradict the idea that sexual dominance and submission is purely a patriarchal act; in few areas do women commonly exert more direct physical and psychological power over men than in the BDSM subculture.

But wait! It can still be seen as patriarchal, because power differentials themselves are patriarchal! Thus, the woman who is turned on by sexual dominance over men is still beholden to the false consciousness of patriarchal ideology, because she’s turned on by power over others at all, and power over others is the essence of patriarchy.

This epicycle was expressed clearly by Riane Eisler—one of my ecofeminist heroes—in her 1995 book Sacred Pleasure: Sex, Myth, and the Politics of the Body:

[E]ven if. . . a certain percentage of men find the notion of being dominated by women who cruelly punish them sexually arousing, and a certain percentage of women also find this kind of sexual role reversal exciting, in either case sexual relations (and thus male-female relating) are still equated with domination and submission; that is, with relations of inequality. . . .

Because the eroticization of violence and domination has been central to the social construction of sex for millennia of dominator history, most of us—and not just women and men actively involved in the S/M subculture—are to varying degrees sexually aroused by sadomasochistic fantasies. . . . [But this is] not the same as pretending that the eroticization of violent domination and submission is politically and personally liberating, rather than further conditioning us to accept domination and submission in other spheres of life. [hardcover edition, pp. 218-19]

According to Eisler, when a woman becomes interested in BDSM, even as a dominant, she “unwittingly become[s] co-opted by the same dominator sexual counter-revolution that is today being mass-marketed by a billion-dollar pornography.” Thus, in an extreme example of false-consciousness theorizing, Eisler says that women viewing their interest in BDSM as sexually liberating, even as a dominant, “seems totally insane. And in the sense of insanity as a failure to perceive reality, it is.” (p. 217)

So, I wondered, reading that interview with Diamanda Galás: would Eisler think of her as “totally insane”? Would Eisler consider her “unwittingly co-opted by the dominator sexual counter-revolution”?

Here’s Galás on her interest in exploring sexual domination over men:

I want to fuck a man in the ass (so far I haven’t had any volunteers; I always ask them and they get nervous and say no) but I want to, because I feel that’s a fundamental part of my relationship with them and to myself. I don’t want to just be fucked--what’s that? I want to experience this other thing. Someone said long ago that men should be fucked in the ass first before they fuck a woman, so they can understand what it feels like to be penetrated in their body. And in this area, I’m all too willing to help! That would be my ideal man, definitely.

Oh yes, we can sit on men. . . but after a while I want to be paid—as an ex-hooker, I want that. Really, I wanna fuck men in the ass—I want to break the flesh, too—and exorcise my violence on them to show them just how much I love them!

Her worldview disturbed me, but her honesty impressed me.

It would take me decades to fully realize—in my mind, and within my own darkest, most hidden flesh—what the hell she was talking about…

[Read the next chapter here.]

Footnotes:

Haggard, in his role as the pastor of a mega-church and president of the National Association of Evangelicals, was publicly homophobic and voiced opposition to gay marriage. In 2006, a male sex worker said that Haggard—a married man—had paid him for sex over three years, and had purchased crystal meth from and smoked it with him. Haggard admitted to receiving a sexual massage from the sex worker, and to buying meth from him, but not to having intercourse. He resigned from his positions at the church and the association; he later admitted he had had a sexually-charged relationship with a male volunteer of his congregation. This sordid tale is told in the excellent 2009 documentary The Trials of Ted Haggard.

Hypocrisy is often seen as a divergence between belief—or professed belief—and action. Of course, it is that. Yet I think this divergence stems from something deeper within: a split within the psyche itself. After all, the contradictory action stems from somewhere in the mind—and that somewhere is shadowy to the part of the mind issuing the high-minded principles.

If the belief is mere “lip service,” mouthed as a bald-faced lie to achieve a specific social benefit, and not sincerely held at all, it is perhaps cynicism more than hypocrisy. The more baffling forms of hypocrisy seem to involve behavior that diverges from sincerely held beliefs.

But in that case, what does it mean to “sincerely” hold a belief that one contradicts in action? Isn’t the contradiction evidence of—even part and parcel of—the insincerity of the belief? These are complicated questions to which I don’t have the answer. However, I can say that—like most humans—having engaged in both hypocrisy and at times lying about my true beliefs, hypocrisy feels different on the inside than straight-up lying about what one believes. It may not be less culpable, but it has—as philosophers say—a different phenomenology.

Alan Watts, in his essay “Spirituality, Sensuality” (in This is It), offers the best description and explanation of the phenomenology of the public, pious hypocrite I’ve seen, in discussing the type of the “saint-sinner:”

the individual who appears in public as the champion of the spirit, but who in private some sort of rake. Very often his case is not so simple as that of the mere hypocrite. He is genuinely attracted to both extremes. Not only does social convention compel him to publish one and suppress the other, but most often he is himself terribly torn between the two. He veers between moods of intense holiness and outrageous licentiousness, suffering between times the most appalling pangs of conscience. (1973 edition, p. 116)

I was terribly torn between and genuinely attracted to both the extreme of radical ecofeminist analysis—which gave me the social-theoretical answers I was looking for—and the extreme of a licentious life (in my fantasies) full of the kind of comely women to whom I was jerking off.

As is likely obvious, I since diverged significantly from Mr. Hargrove’s views, particularly his anti-porn views. We had been very close; aside from my father, he was the greatest influence on my earliest development as a writer. But as I worked through much of the life material that became this book, I dropped out of touch with him. I was grateful for the role he had played in my life, which made me all the more terrified he’d be disappointed in me.

As part of a recent effort to “close loops” in my life, as I become more aware of mortality, I wrote him, sharing about my life and intellectual journey in the two decades since we’d last communicated, and sharing with him my fear of his disappointment, which had kept me out of touch. I had no idea what I’d hear back.

Mr. Hargrove wrote me the most gracious letter back: “I can’t tell you how sad it made me to think of you worrying about my ‘disappointment.’ Do I think your views are wrong on several very—fundamentally, urgently—important levels? Yes. But am I delighted to know your great, questing heart is out there thriving in the interstices between the obvious categories, still seeking meaning and justice and liberation? What teacher would want anything else?”

We have since rekindled our correspondence, for which I’m extremely grateful. Though I still wince when I show him my writing.

I’ve come to see that most political ideologies can be compared by what they deem to be the “root evil” of the problems they address, and when, where, how, and among whom they believe that root evil arose.

Some ideologies posit a morally-pure primordial paradise, age of innocence, or golden age before the entrance of evil in a “fall from grace.” The emblematic example is, of course, the Bible, which posits early Eden as a morally-innocent paradise, followed quickly by the fall when Eve eats the apple.

For “anarcho-primitivism,” an ideology I held loosely along with ecofeminism, the golden age was hunting-gathering tribes and the fall from grace was the development of agriculture and civilization. For the more misanthropic versions of “deep ecology,” which I also held loosely, the golden age was wilderness before humans, and the fall from grace was humanity itself. And for ecofeminism, the golden age was a supposed era of peaceful matriarchy, and the fall from grace was the development of patriarchy; this view was advanced forcefully in one of the bibles of my ecofeminist days, The Chalice & the Blade: Our History, Our Future by Riane Eisler. (For a book sharply critical of the idea that there was a period of widespread peace-loving matriarchy before the advent of organized patriarchy, see The Myth of Matriarchal Pre-History: Why An Invented Past Will Not Give Women a Future by Cynthia Eller.) All these ideologies argue that a golden age can be revived, in a contemporary context, by following their prescriptions and becoming activists (or cult members) for their causes.

Other ideologies, such as Marxism, and transhumanism/singularitarianism, do not look backward towards a golden age or paradise in the past (though Marxism does posit a pseudo-paradise in its concept of “primitive communism.”) Rather, they focus on a posited paradise/utopia/heaven to come, such as world communism (in Marxism) or the singularity, in transhumanism.

Many commenters have pointed out that Marxism and transhumanism have strong overtones of Judeo-Christian messianism, a utopian messianic age and world to come. (See, for example, “Messianism and Marxism” by Warren S. Goldstein, and, on transhumanism and the singularity, “Of God and Machines” by Stephen Marche.)

None of this should be construed as a suggestion that “men just can’t control themselves” around women, or that women somehow “provoke” men’s sexual transgressions. Yes we can control ourselves, and no women don’t “provoke” our transgressions. I’m writing here about the way this constant internal horny-drug drives many (most) hetero men to seek release by masturbating to nude imagery of women. Anti-porn feminists consider masturbating to media featuring women posing nude or having sex to be a form of direct sexual violence against women. They question whether a woman can truly “consent” to pose nude or have sex for money, in a society of unequal sex relations. As we’ll see later, female sex workers have much to say on this topic. They don’t tend to appreciate anti-porn feminists conflating male customers who are quietly and politely paying them their requested rates and respecting all specified boundaries, with violent men violating their specified boundaries and inflicting physical violence.

This was 1996, just as the Internet was gaining steam, so it was before the problems with the “nice guy” and the “friend zone” had become widely discussed and analyzed by women online. I dive into the “nice guy” and “friend zone” issue in detail in my chapter “The World’s Greatest Friendzone” (forthcoming).

The irony is that ecofeminism is highly critical of the way Christianity shames and demonizes sexual desire and pleasure, and yet—as a devout ecofeminist—I had managed to reconstruct within myself the emotional experience of the Christian sex-guilt-shame complex perfectly. And I wasn’t raised religious, or with any sex-shaming whatsoever.

I took on an extreme, religious-level shame complex about my sexual desire, as a teenager, entirely outside of family influences, simply through reading works of political theory.

The ecofeminist books I was reading that were critical of porn, particularly Pornography and Silence by Susan Griffin and Sacred Pleasure by Riane Eisler, were emphatically against Christian shaming of masturbation, and passionately in favor of exploring self-pleasure. But as I knew all too well from… ahem… first hand experience, when it came to male masturbation, there was a strong tension between ecofeminism’s generally pro-self-pleasuring stance, and its stance that men’s self-pleasuring to sexually-objectified imagery of women is literally violence against women. That’s a heavy rap against the way the majority of one sex whacks off.

Ever since the founding of Playboy and the advent of easily-accessible pornography, for the most part, that’s how straight men masturbate: with the aid of two-dimensional sexualized images of women. If those images literally are violence against women (as anti-porn feminists claim), then by extension, male masturbation, as it is actually practiced by the vast majority of men, is literal violence against women.

That’s a helluva view. It’s one I believed. But since my masturbatory habits—like most men’s—involved sexualized imagery of women, I developed tremendous shame around my masturbation given these ideological views. My philosophical context could not have been more different from Christianity, but the intensity and emotional tenor of the masturbation shame I felt once I became a devout ecofeminist reached the level of what devout Christian men and boys often feel about their own wanking. They and I felt our spankin’ made us sinners.

It’s not difficult to see why the Church thought so. Galás identifies openly as a satanist, and her early albums previous to that performance were entitled Litanies of Satan and You Must Be Certain of the Devil. She performed this work at the cathedral’s altar topless and covered in seeming blood. The photos of the live show inside St. John the Divine (printed in the album liner notes) are stunning, given their unlikely location. I wonder if whoever allowed her to perform this work in the cathedral kept his job. In an interview in the anthology Angry Women, Galás claimed that her albums were “take[n]. . . to priests for exorcism.”

The bracketed “[sarcastically]” is in the original. Note that in the BDSM world, bringing race into sexual play between white people is generally considered off-limits. When one or more of the kink players is a person of color, they sometimes choose to bring race into role-plays and consensual power exchange. For a nuanced exploration of this dynamic, see the powerful 2018 documentary The Artist and the Pervert, about the Black kink educator Mollena Williams-Haas, who is a submissive, and her white Austrian husband, who is her sexual Dominant.

For a contemporary defense of the feminist theory of false consciousness, see “Feminism, false consciousness & consent: A third way,” by Shallyn Wells.